Men of Mother’s and of Mine: Redeeming the Inner Masculine in a Finnish Folktale

A Jungian Analysis of the Finnish tale by Colleen Szabo

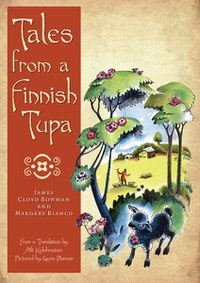

(Once upon a time there was an old man and an old woman who had nine sons, but no daughters… This interpretation of the wonderful Finnish folktale The Girl Who Sought Her Nine Brothers is based on the copyrighted version found in Tales from a Finnish Tupa, by James Cloyd Bowman and Margery Bianco, first published in 1936 and now published by the University of Minnesota Press. A very similar version can currently be found for free online at D. L. Ashliman’s online folktale collection under the category “The Brothers Who Were Turned Into Birds” as The Little Sister: The Story of Suyettar and the Nine Brothers.)

(Once upon a time there was an old man and an old woman who had nine sons, but no daughters… This interpretation of the wonderful Finnish folktale The Girl Who Sought Her Nine Brothers is based on the copyrighted version found in Tales from a Finnish Tupa, by James Cloyd Bowman and Margery Bianco, first published in 1936 and now published by the University of Minnesota Press. A very similar version can currently be found for free online at D. L. Ashliman’s online folktale collection under the category “The Brothers Who Were Turned Into Birds” as The Little Sister: The Story of Suyettar and the Nine Brothers.)

Only when we confront the darkness with honesty and humility can we hope to transform it. — Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee, The Return of the Feminine and the World Soul

Only full, overhead sun

Diminishes your shadow…

— From Enough Words, Rumi

This story of feminine redemption stands out for me because of the somewhat unusual constellation of characters. Using the Jungian perspective that such stories depict an inner relationship which may also be manifest in our relationships with others, we see that here nine inner brothers “carry the torch”–the woman’s desire to develop intimacy between her inner masculine (the brothers) and her younger feminine aspect (the daughter). This inner masculine aspect which desires intimacy is usually depicted in European fairy tale by the lover. I also like that the story is really about an old mother–like me, I suppose–despite the fact that the featured character is a maiden, a young unmarried woman. The protagonist maiden Vieno represents the mother’s inner maiden. It seems that as a maiden the mother lost a certain kind of connection with her masculine self, with powers such as self-protection and self-assertion, and now she must pick up where she left off all those years before.

The tale’s about someone who’s already got grown sons with mature masculine powers, sons who can go live by themselves, who can make important requests, and who can threaten to leave if not fulfilled. The fact that the woman has a baby (Vieno) in a few weeks–brought by ethereal spirits, by fairies–points to the fact that she’s not really having a baby. She’s birthing, perhaps more accurately rebirthing or reacquainting herself with, a heretofore strange aspect of self. This strange aspect of Vieno, and the ogress who appears along with her, are going to reconnect the mother with the undeveloped masculine aspects–aspects held in her daily life by the ten men in her world: her “old man” husband and her nine sons. (Ten is an archetypal number of completion, signaling endings and thus new beginnings.)

Both the fun and the confusion of a symbolic approach to story is that we hold the possibility that the characters are completely unknown in waking life to the protagonist, or they could be physically represented in our lives by those around us, by our own behaviors, and by literal sons and husbands, mothers, and brothers. Interpretations must take this range between inner and outer experience into consideration, and straddle the fence between the two. This can be difficult, but there is one fast rule: the characters are surely within, even if they are not manifest without. Of course this fairy tale woman’s outer immersion in the masculine, this life encompassed by men, is quite common for women in a patriarchal culture. I went along for a long time in this fashion myself. I was playing a man’s game, since that was the only one I knew, and it served me fairly well–until it didn’t. As a young woman, if there were any men about, I saw myself through their eyes; I considered what they approved of, what they wanted, first. I valued what they valued. I often acted out the feminine side to their masculine powers, and thus had no reason to claim and express much of my inner masculine potential.

This role was easy for me, because I was like Vieno, whose name means “gentle, mild”. This is the sort of woman that most men, and maybe women, in my culture prefer, for intimate relationship as well as daughter or sibling relationship. Why not? Such people are like comfy couches, rarely showing their teeth; they don’t contest boundaries, they ask little or nothing from relationships. They generally make life easier for us, and thus hold an important role. Jungians would call this mild woman a sort of “anima woman”, someone who instinctively acts out men’s ideal of the perfect woman to fall in love with. Combine this gentleness with some beauty, and men can be quite enthralled. But if we are lucky, there comes a day when this vieno female is no longer sustainable. The inner pressure to holism and personal development, to bringing to waking consciousness the unbalanced truth of our relationship with our inner shadow aspects, can become too much. Such moments of crisis and opportunity are often depicted in fairy tales.

So the young woman Vieno is an inner psychic aspect of the “old woman” mother–some aspect of her own young womanhood, the time when she left behind the ability to protect herself, to say “no”, to follow her individual true choices whether others will approve or not, or to manifest or bring forth some creative gift. To help break her of outdated old habits, the mother is delivered an ultimatum by the eldest son. If she does not decide to get going on her new version of consciousness, her new identity, he and his brothers will disappear. Her youthful masculine energies, deserted in those days of youth, will depart; they cannot wait forever to manifest. Menopause, with its lessening of estrogen influence, usually signals increased embodiment and expression of masculine energies. Women, especially those who have been dedicated mothers or caretakers, will then often move toward balancing out their youthful, feminine, constant concern with human relationships. They will begin to shift toward the more masculine ability to be concerned with their own creative life, with their own personal development and personal goals, for example. The mother can make no promises to her sons; she has never done this, it could be a once-in-a-lifetime effort she will initiate. Will she manage to do something different this time, or will she do what she has already done nine times out of ten?

The mix up with the ogress is the clue both to Vieno’s tasks, and to the origin of the mother’s situation from the time of her own birth, and her own youth. The spindle is a feminine tool, representing feminine powers of spinning separate threads together into a strong whole, the skill women (and men) use in creating strong relationships with family, friends, and ideally the natural world and the unseen worlds. The axe, in contrast, is a masculine tool, all cutting tools being symbolic of the masculine ability to do the opposite of spinning. Swords and knives and axes represent the ability to cut, to discriminate, to discern “this, not that”, to make unattached decisions about what works best for us, to pull away from emotion and see how we might be manipulated by others, and to entertain different perspectives on our life-denying entanglements. It is notable that the mother is indecisive in the beginning; she just smiles when the sons ask her for a sister, probably her habitual response to requests. She may be having trouble making a choice, trouble clearly seeing her current situation and the ways in which it is no longer sustainable. She doesn’t have a blade to cut the ties with her old ways of identifying as the nice mother and wife.

Somewhere in the mother’s youth, there was a powerful experience which caused a separation between her masculine (brothers) and feminine (mother and Vieno) selves–the separation that is actually the norm for our socialization process. The ogress, who personifies with her switching of spindle for axe this separating aspect for the story line, “works” for the masculine. Later in the story she will, quite literally, do this work, but in the beginning she shows her masculine nature by her ability to change the feminine spindle into the masculine axe handle. I might cast the ogress’s origin in the mother’s psyche as the negative judgment–fear and anger which a malecentric society projects onto the authoritative, assertive, or aggressive female. Suppressed but powerful, this ability to aggression, assertion, and authority lurks in many women’s psychic shadows, sometimes lurching into view as PMS, which is then labeled “hormones”, the supposed chemical origin of our monstrous monthly transformation. Many women fear this inner ogress, whom we condition ourselves to try and forget, and imagine ourselves as always (or at least almost always) compliant, assuming the aggressive one we’ve been deconditioned to has no toehold in our psyches. It’s just hormones.

Many of us imagine we are perennial “good girls” despite some rather pushy behaviors, while some of us actually are as compliant as Vieno’s mother. Since “good girl” is socially sanctioned, we may cast ourselves in that role, identify ourselves thus–even despite actual behaviors. We put on that face to the public, for example, though we may be disrespectful and even cruel to self, to lovers, friends, and to family. Being aggressive, insistent, forceful, angry, pushing your will onto others’”these are archetypally masculine behaviors. They are the axe of the boundary-setting gender, whether it is a man or a woman committing them. Therefore, in many cultures this behavior is considered especially ugly and monstrous (like the ogress) in a woman, though taken too far it won’t win friends no matter what your gender. Notice that the mother’s position in the tale is one of submitting silently to her masculine sons’ demands. She is eminently passive; she doesn’t even talk, just as Vieno will be muted later in the tale. This extreme behavior is the story’s descriptive code, explaining to the audience that Mother has to learn about her suppressed, aggressive inner ogress.

The spindle is also an ancient feminine symbol of the Fates, Norns, and Wyrrd sisters, a symbol used in fairy tales like The Sleeping Beauty. So the spindle could be an indicator to the sons that their mother was moving forward in her spinning of a life of destiny, towards further personal development. The axe is, rather strangely, morphed into an axe handle, not an axe, when the ogress sets it by the door. Could this refer to the fact that the old way, the way of always producing sons, of submitting smilingly and silently to their requests, is something our protagonist already “has a handle on”? Or does it indicate she still lacks the masculine ability to assertion and self-protection, since the blade is missing?

Vieno’s birth is then a return to a road not travelled, a picking up of dropped stitches, the road which Vieno and the ogress will soon enough traverse, for just as the baby was born in a few weeks, we are not expected to take literally the years of Vieno’s life. The point to her impossible maturation is that Vieno represents the threshold of womanhood. She is adolescent, and thus we are here referring to the mother’s life experience at that time, to that developmental stage. I love the important role here of grief, of tears, since I have focused on them as crucial on my own journey of self-reclamation. Though women’s crying has generally been denigrated to sheer feminine weakness in my patriarchal, Euro-Western society, it hasn’t always been so, as this tale informs us. Tears were once respected for their magical cleansing and transformative powers, for example, in the days when women’s purgative grieving was considered an essential part of death rites and memorial ceremonies.

This focus on emotions begins early in the tale, a way of portraying the most common emotional gender split. The sons, as representative of the masculine aspect, get angry with the mother very early on. Anger is as important as grieving here, because anger is the emotion most obviously associated with aggression and, therefore, self-protection and boundary-setting. In my society, women do generally get to cry, which is appropriate to the watery emotions as part of the feminine archetype, while men get to be angry–masculine emotional element is fire. Vieno’s feminine tears of grief and loss for herself and her mother are the start of something big. It’s initiated when a truth is revealed, the story of the switch, of the division between the masculine and feminine crucially experienced in adolescence, when men must often leave behind much of their feminine aspect, and women their masculine. It is a great loss, the loss of the inner brother or son aspect in the case of our protagonist(s). The woman/women cry because they have connected deeply with the truth that something has been lost. The sons realized this loss, too, the cause for the expression anger towards the mother. The wisdom of this is that the same unwanted event or condition is capable of eliciting either feminine grief, or masculine anger.

The objective for our holistic personal development is the balanced place where the twain meet–where we can experience, admit to, and express both fire and water, with some wisdom and consciousness. It doesn’t count if you have to get drunk to do it, or you do it and then beat yourself up about it, or you do it and then blame it on someone else, etc.–“it” being the emotional expression you do not habitually express, the one which seems monstrous to you and maybe to others. A real-life mother such as the one portrayed in the story could very well be a pushy, angry woman, in fact, but if she does not know that, if she thinks it is her children’s fault for being such terrible sons, or her ogress mother-in-law’s fault for being controlling, for example, she is still rejecting that aggressive aspect of herself. She is projecting her anger onto others, and still needs the self-revelation which this story describes.

The mother does a wise and wonderful thing; she creates a round tear-loaf to guide her daughter. Just so, a woman’s tears of grief for what has been lost have the power to lead her to the truth of her situation regarding her own inner development. Tears and grief help us to reconnect with that which has been lost along the way. We have inevitably left behind parts of ourselves for reasons of survival and conditioning and harmonious (or inharmonious!) relationships, relegating these things to shadow. The loaf is sacred mother-bread; it implies the ability to, and the support for, discovering that which is needed for nurturance, for healthy growth and development on all levels of experience. The circle is the symbol of holism, of feminine all-inclusiveness and of the soul; the discovery of our inner and outer sources of nurturance and support is a huge part of our journey to wholeness within a patriarchal society. The mother collects the tears in a feminine container, a jar made of earth–what a beautiful metaphor for the correlation between a woman’s tears and the elemental, purifying grief-and-water-wisdom which flows over the very Earth itself! Every woman shares this grieving with the Earth as an embodied carrier of Earth’s feminine soul. Men with developed feminine sides can partake of this nurturing grief-bread, of course.

This rolling bread also reminds us of the great grain goddesses, representatives of the annual vegetative circle-cycle of birth-growth-maturity-death-rebirth, a prominent aspect of earth wisdom for agricultural peoples. Ancient Greek grain goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone come instantly to mind. After Demeter’s daughter Persephone descended to the realm of Hades to become his wife, a sort of joining with the masculine side such as this tale depicts, Demeter spent months wandering the earth, grieving for her lost daughter, just as Vieno grieves and searches for a lost and transforming aspect of self. Vieno also undergoes a sort of Persephone-like descent into the dark when she is transformed into the ogress and loses the power of speech. Traditional Finnish rye bread is actually shaped like this bread Vieno follows. This disc-shaped rye bread was (is?) baked rarely, and stored just beneath the ceiling, strung like huge beads on wooden poles.

Pilkka, Vieno’s dog, is also named for his origin; he is “mockery, ridicule, scorn”. It seems a strange name for a beloved companion, but ridicule is a common socialization technique, and that is what Pilkka’s job is–to protect his mistress from feeling the grief of rejection, of belittlement and scorn, which she would have encountered if she had acted “like a boy” as a child, and “like a man” as a woman. Perhaps the memory of having been belittled is part of the grief that Mother/Vieno is now in touch with. Pilkka is spotted black and white to indicate, for one thing, that he represents a separated condition within gender-oppositional experience and behaviors; a grey dog would indicate a melding of the feminine and masculine opposites.

The frequent use of charms (Roll, roll, round bread roll…) in folk/fairy tales indicates the sacred nature of the soul work being storied about, in a form which contemporary America would describe as magic. This magic is a big part of what we experience as the shapeshifting space created by such stories, spindle to axe handle, maiden to ogress, dog to dust. The wheel-shaped, charmed tear-bread works quickly to bring in the ogress. She has been there waiting in the tears all along, though just as Vieno doesn’t know the ogress when they meet, the mother-daughter character is still unable to own these qualities embodied by the ogress. Again, rejected parts can be felt as sadness (Vieno’s tears) as well as the ogress’s irritation and anger.

As is the case with all such fairy tales, this shadow character, the ogress, may seem malicious, and the dog victimized, but that view is the old view. What Pilkka is really trying to avoid, to guard against, is Mother’s/ Vieno’s discovery that this ogress, though perhaps rejected in daily life, is powerful and useful to the mother’s psyche and to her life. The dog’s guarding of his mistress was useful once, allowing her to fit in, to survive, to get along, but those old ways are not appropriate now. The fairy tale’s transformed energies, such as Pilkka’s protection services, will usually disappear from the story somehow by the end, but their death or disappearance is really a metaphor for the transformation and assimilation of their energies. Pilkka’s disappearance is a metaphor for making these once unconscious dynamics conscious. Energies which were once repressed or projected onto others have now been claimed, and thus will not be experienced in the previous form.

This story cleverly insinuates the association between Vieno, whom we might imagine as the “mild”, kind, and polite aspect of the mother, and the ogress, by having the ogress speak oh-so-politely and patiently to Vieno, in a motherly, considerate way. Thus we are introduced to the possibility that all is not as it seems, and a nice Momma can be hiding an inner ogress. Mother/Vieno’s mild manner could in fact be the same thing as the ogress’s switching of the spindle: a way of manipulating others. We all begin our lives learning how to manipulate the world, and politeness and gentleness and passive tears, as well as aggression and anger, can be used to this end. The story begins with the sons figuring out how to manipulate their mother, reminding us of this basic endemic aspect of human relatedness. Though it may seem that the mild woman is always compliant, her very compliance is paradoxically a way to get what she wants from others; to be treated with kindness, to be esteemed, to retreat from confrontation, etc.

In fact, Vieno herself cannot see through the ogress’s bogus, manipulative politeness and concern. She doesn’t understand this purpose to which her characteristic mildness may be currently used, since it’s essential to identifying as the female goody-goody that we believe we are unselfish, that we care nothing for our own wants and needs. Her dog, who represents a more instinctual aspect of Vieno, is the one who gives warning that something dangerous lurks beneath the façade, something having to do with survival. Instinctual survival response is part of what forms our early behaviors and personalities, our defenses and fears, and the original response which became habitual was originally instinctual, a way to get from the world what we needed.

However, the story is correct in informing us that mature transformation, whether late adolescent or even late adulthood, requires going beyond the boundaries of our early instinctual response, at least those which are meant to protect us from social castigation, which is Pilkka’s job. The protagonist must get past this guardian of the original response, however important he might have once been. The theme of water comes in again soon enough, with its restful, purifying, and healing properties. The sparkling water Vieno, Pilkka, and the ogress come upon refers to water of the spirit, of purifying inner light–a pool, because of its stillness, is symbolic of self-reflection. The dog may be trying to protect Vieno from self examination, but three’s the charm, though the truth will have its sting. As in the myth of Narcissus, the pool acts as a sometimes emotionally charged mirror of the soul. In such a pool, the truth of who we are beneath our survival behaviors is revealed.

The pool of revelation is approached three times because fairy tales always indicate the sacred nature of inner transformational work by three tries. The protective dog, with whom we all sympathize, has to go before Vieno/Mother can begin to experience her inner ogress. The ogress is as compelled by the tear bread as is Vieno; she follows it, too. They are one, maiden-mother-crone. As the unsocialized, more assertive aspect, the ogress knows what developmental change is needed. Her anger at the dog mounts, until it literally disappears the dog. The dog’s role as protector from the mother’s inner experience of anger and aggression means that the ability to connect with and express anger will spell its death. From the perspective of Vieno’s/Mother’s inner growth, the dog is indeed Paholainen, the Devil, the father of lies, just as the ogress claims. We lie to ourselves when we imagine we do not experience anger, we claim that it is not useful, that we are only that which our society has conditioned us to imagine we are. For a woman who has kept her anger under wraps for years, the anger itself, the ogress, may now become the teacher. The ogress’s statement, “Now we shall see”, can be taken quite literally; without the old feminine way of avoiding anger, Vieno/Mother will see things she never saw before, such as the nine brothers who have disappeared in anger, those whom Vieno has literally never seen.

The new way of seeing is also symbolized by the character and body switch, the ogress’s baptismal magic which allows Vieno to witness life from the assertive side of the fence she had always imagined herself oppositional to. Vieno now literally experiences this ogress aspect, a previously rejected aspect of self: voiceless, dumb, as it always was, anyway. The ogress within Mother/Vieno wasn’t welcomed into daily life, and therefore did not develop the capacity for expressive language. It was unconscious, brutish, and undeveloped, playing what seemed to be subversive tricks on the woman as shadow aspects will, like kicking dogs and switching omens of good fortune. So now the ogress has taken the role of beautiful Miss Goody-Goody, while Vieno is forced to explore the old, ugly, unwanted aspect she once spurned, here in the land of men, where anger and other forms of aggression are acceptable as part of the natural landscape. The men aren’t exactly welcoming of the ugly old woman-sister, this unknown who cannot speak for herself; they ask “from what far country do you come”, indicating their unfamiliarity with her. However, they do accept that the mute old woman is useful; she has a place in the psyche, in this land of the masculine. That the brothers live in a garden indicates that we are in the inner terrain of the abundant, growing, creative soul, which uses its innate wisdom of growth and development, and its connection with the divine, to contain and drive our inner work.

While the former ogress keeps house with the brothers, the mute ogress/Vieno will now do men’s work, herding cattle. She will try to feel her way into some masculine aspects of herself which were previously unknown to her. Cattle have long symbolized a sort of wealth, an internal state of abundance and security in psychological terms. When symbolized by the cows, this state is often considered to be the provenance of the masculine, at least in a society in which most material wealth is owned by men. This is the realm of the enlightenment god Apollo. Herding is masculine in the sense of being a job of protection–the patriarchal protective father aspect. Herding also entails watching (seeing) and counting, two archetypically masculine activities.

Vieno/Mother will have to endure some travail before she can birth this new synergized way of being into a world where there is room for both masculine and feminine ways of being. She must spend some time in an unprotected place, enduring whatever comes her way, without reverting to her socially conditioned behaviors’”behaviors from which she now, through the role switch, has some distance. While alone and out of doors, she is literally connecting with the healing powers of the earth–doing ecotherapy by putting her tears in an earthen jar, if you will, and learning how to connect with her natural self, away from the socialization in human relationships, as vision questers will. Wind is mental activity, rain is watery feminine emotion, and the noonday sun is the full-on power of the fiery masculine, which includes the protective emotion of anger. She is learning balance from all four elements, in the traditional wisdom way.

Often a woman who acts very feminine and has no ability with anger, is unable to be alone, without the protection of a man. They feel too exposed, as does Vieno in the meadows. In society, a beautiful young woman should generally not be alone long herding cattle; she would not only be a poor guard for such property, due to a lack of fighting skills, but she would be exposed to being forcibly taken herself. Such obvious dynamics which are found in the animal kingdom are part of what creates our human behaviors and personalities, which are then reinforced by society. However, Vieno is at this time an ugly old woman, so she is relieved of some of the fear which might accompany being vulnerably female and alone and attractive in the world of masculine power.

In Greek myth, Apollo’s cattle and his noonday sun represent the embodied experience of radiant masculine holy abundance. Watching cows implies mindfulness, a wise skill. Just so, when we are doing inner work with anger and other emotions, we must be watchful, so that the heat of emotion does not take us over in some stampede of uncontrolled, animalistic behavior. We must learn to “keep it together”, to feel secure and grounded in the moment and with what we have, with who we really are as humans and as spirit and soul, despite the vagaries of the weather and the seasons of our lives and the criticisms and expectations of those around us. Cattle embody the dichotomy between the bull’s powerful masculine aggressive fire and the feminine, more placid watery element of the cow’s temperament. Perhaps Vieno can cultivate and recognize anger from this natural, elemental perspective, and then she will not have to fear it. She will discover its necessity and its usefulness, and how it fits existentially into the embodied animal-human experience.

A lack of alone time can be problematic for women’s development, particularly in developing a wise elderhood or croneage, as can a lack of time in nature. The ogress Vieno is given time for healing and contemplation here, some ecotherapy if you will. The beauty of telling one’s own story is also here, encapsulated within the larger fairy tale story. Vieno, as cattle herd, is free to express herself alone, outside of relational obligations and household duties. She sings her story to herself and to the soul of the fields, to the cattle and to the skies. Women naturally cotton to the expressive healing arts, and talk therapy is based entirely on the opportunities for holism within the storytelling experience. In this storying, Vieno is working with the burrs in her shoes, the things which create discomfort in her way of walking the Earth. She’s working with the bread-stones of remembrance, the heavy memories of ridicule and belittlement which were a part of her socialization, and which she was forced to eat growing up.

These bread-stones can keep her from experiencing proper relationship with the inner mother, and can keep her from truly mothering herself, since bread is significant of the great grain goddesses, feminine counterpart to the gods of the cattle. After decades of mothering others, concerning themselves with others’ wants and needs, women must often make this shift towards mothering themselves, discerning that which feeds them on all levels, including the level of soul and spirit, of creative expression. These old memories were what she once gave the ogress to hold. She had pushed them away from consciousness, so she would not feel angry about them, since anger was not considered appropriate and did not help to make life any easier. Giving those angry burrs and stones to the inner ogress, and staying sweet and nice in her behaviors, has reached the tipping point; she can no longer hide the inner distress. Like many folks who come to this tipping point, she is what we call now in our society depressed; she is “more sorrowful than she has ever been.”

Vieno’s work in the meadows, her inner watching and storytelling and enduring and feeling, bears fruit one day; the brothers hear. She has opened a new line of communication between her feminine and masculine aspects; she has crossed the river which once caused her to remain stupid about her own anger and grief. The chant (sadly not included in the online version) she sings is a song to the masculine, to a very Apollonic aspect, in fact: bright day. Trees are here, too; the Finns, like some other northern peoples, are tree-folk. Trees, like other natural beings, represent sacred aspects of human and non-human experience on Earth. Of course the specifics vary–my main source for interpretation is Celtic, which seems to be a fairly accurate one when applied to Finnish lore. Fir, mentioned in Vieno’s song-story-charm-prayer, is a representative of elation, of fear and trembling, and of experiencing divine energies which are always holistic. This interpretation would be useful here; the straight sky-high firs are like lightning rods, bringing down ethereal energies needed for her to rectify the dualistic split between her masculine and feminine sides. Birch is universally a tree of purification and new beginnings. It is associated with water, and with maidenhood in the case of the white birch. Vieno’s singing, her days spent in the outdoors, and her weeping are all ways of purification, of “out with the old, in with the new”.

Vieno’s humble experience as old and ugly is often portrayed in fairy tales for women. It’s an experience of humility which drops us below the ego’s radar, and allows us to move into the realms of soul and of spirit where the world’s appearance ratings don’t exist. Women are particularly judged according to looks, another archetypal association as the object of desire. In contrast to Vieno’s humble condition, the ogress is now “head of the house”, and has “everything she could wish”. Does the ogress act more self-assertively than Vieno’s mother once did, since self-assertion is assumedly needed to act with authority as “head of the house”? Does she actually bully the nine brothers into giving her what she wants? Or did the mother always get everything she wished before, with her mild manner of manipulating? I suppose it’s moot, since the ogress and the servant Vieno are one and the same. Her Vieno aspect is now involved in a very different experience in which she has little or no control over her situation, as humble servant to the nine brothers and to her alter ego, the ogress. She now knows what it’s like to be the suppressed one.

Most interestingly, Vieno, who is working with the emotion of anger, asks in her prayer that she be carried home “harmless”. Many women, including myself, who witnessed as a child or later on the death-dealing destructive potential of anger, whether expressed by men or women, reject it utterly. This makes sense, until you discover that its rejection subjects you to an unbalanced life of suppression and fear, a life of too much dependence on others for your security. Many women associate men’s emotional makeup with war and the angry, insensitive, masculine rape of the Earth–or of women, and that is good reason to reject it utterly when you don’t really understand its deeper nature or the harm and retardation caused by its suppression. Vieno is concerned that, if she allows herself to feel anger, she might become destructive or might harm others, as all emotions can be used in more or less egotistical ways. Vieno asks the sacred masculine “bright day” to help her come home to her authentic self, and cause no harm in the process. Notice she does not ask to be unharmed; she asks not to harm. She has moved beyond her self-protective modus operandus in regards to the masculine, to a more holistic, crone-like concern for how her way of being in the world might affect all, human and non-human. This is the crowning attitude of healing/”wholing” expressed in the Hippocratic oath, “First, do no harm.” For what is the purpose of healing, if not to move out of harm’s way, to stop hurting ourselves and others?

Vieno’s complaints about the ogress’s burrs and rocks have here been addressed; the dulling of the knife remains. Knives, as referred to in reference to the axe above, are masculine tools, symbolic of a skill women must develop in order to do productive inner work–the skill of discrimination, of being able to separate things into their constituent parts in order to understand them. The ogress in the kitchen, whom we could say is now representing the mother before the coming triune transformation of crone/mother/daughter, doesn’t want to use this discrimination, this masculine ability to cut through the sea of experience and memory and emotion the feminine principle swims in. So she keeps dulling the knife, rejecting the idea that the masculine ways of being could help. She’s both representing the former knife-dull state in need of transformation, and presenting the tests to be met by the transforming Vieno with her stones and filth and muting.

This cutting skill, when combined with some emotional energy, really gets things rolling, as Vieno puts it symbolically in her bread chant. The knife of discrimination can reveal emotion’s parts, its justifications and origins, and what it tells us about ourselves and our world, or our conditioning. Most mothers, even the ordinarily meek, know the fearless bear-like protective anger which comes up when family is threatened. Beneath our gentle demeanor, appropriate with young children, lurks the anger we might have been attributing to men, yet we also know this thing in a slightly different context in a culture that insists we sheath our claws. This mother-anger can be used to protect ourselves, too, to help set boundaries so that we have authority over our hours and our behaviors and our personal space. Perhaps we with dull knives habitually gave others what they wanted even if it meant devaluing ourselves; we let them steal our cows, our valuation, and turned our eyes in the other direction.

In the ritual at noonday, the masculine sun’s power is used to work the charm of bringing light to these previously dark or ignored aspects of the woman’s psyche in balance with the element which the ogress used to switch roles initially, the watery feminine element. Balance between the masculine and feminine, between anger and tears, is now possible. Noonday is the height of sun power, the highest possible illumination of Earth. Vieno’s “exorcism” in the kitchen is pretty interesting; we are reminded of the ogress’s prediction, “We shall see.” Vieno enters the kitchen with her masculine allies behind her, in a state of self-imposed blindness, saying that her eyes “pain her”.

Her old way of seeing, whether through the ogress’s viewpoint or the old mild Vieno, caused and presently causes some sort of suffering, the suffering of the disassociation of inner masculine and feminine. The suffering was originally expressed in the story specifically as grief over the loss of her brothers. The reverse baptism ritual in the kitchen will dramatize what is usually, for most of us, not quite so dramatic, as it usually takes a series of small realizations rather than one big event to change one’s inner landscape. Yet, for some, there will be healing moments such as this. The very famous song, Amazing Grace, speaks of this moment Vieno is about to undergo. The line “I once was blind, but now I see”, sings of these countless, daily, human revelations. They are part of our heritage as spiritual beings.

The first baptism ritual in the pool–the purification of the eyes–is reenacted, and it reverses Vieno’s ugliness once embodied by the ogress. “Send her away”, says the brother, though it is only the old viewpoint of the ogress that is sent away (in the online version, she is burned in the sauna, burning being a fairy tale option for the disposal of unwanted aspects using the purifying element of fire). The ogress, as an important aspect of Vieno/Mother’s holistic self, shapeshifts away from the old way–the ugly, rejected way–into the new, light-blessed way of understanding and accepting the inner masculine. Now that Vieno understands the ogress as a thing of natural beauty, the old, ugly form cannot return. They all move into the new birch-tree beginnings; the tenth time was a charm, and the round bread Wheel of Fortune has turned favorably for the woman’s inner family.

Though we tend to cringe internally at the emergence of such inner ogress aspects for fear we will become the ugly one, in fact the ogress’s emergence only presages a balance between opposites. In this case balance likely enhances the mother’s ability to speak her own mind and pursue her own path, less dependent on old habits and on old ways of seeing herself. She may be more comfortable and secure when alone; she may experience her life as more abundant and actually have less need to manipulate others. She may be able to cultivate a different sort of life, one which allows room for her own anger, self-nurturance, abundance, creativity, agency, and inner authority.

Colleen Szabo is a writer and artist currently living in Michigan. Her writing includes poetry and nonfiction: essays, articles, and reviews. Her formal education is in psychology: a Bachelor’s degree from the University of New Mexico, and a Master’s in Transpersonal Psychology from the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, in Palo Alto, CA. Find more of her writing, including essays and symbolic film reviews, at colleenszabo.com.