There was once a princess who, while still very young, was betrothed to a king much older than herself. The king’s first wife had proved barren and at last, after a long illness, she had died. The king sought a new bride, in the hope that she would give him an heir. The young queen was frightened, so far from her own country, and pined for home. Although the king was kind to her in his way, he was an old man and had little patience with a young woman’s follies and regrets. When a year had passed, the queen gave birth to a daughter, and this proved to be the only child she was to bear.

There was once a princess who, while still very young, was betrothed to a king much older than herself. The king’s first wife had proved barren and at last, after a long illness, she had died. The king sought a new bride, in the hope that she would give him an heir. The young queen was frightened, so far from her own country, and pined for home. Although the king was kind to her in his way, he was an old man and had little patience with a young woman’s follies and regrets. When a year had passed, the queen gave birth to a daughter, and this proved to be the only child she was to bear.

Despite the sex of the child she was welcomed by the old king with an open heart, for he was grateful to see his line continued and his person immortalized in the flesh. The court and the kingdom followed suit, and nothing was too good for the Princess Hyacinthe. She was a lovely child, with pale, almost colourless skin, rose red lips, and hair as black as a raven’s wing. As she was as sweet and docile as she was beautiful, everyone was soon in love with the charming child.

Everyone but the queen. As the princess grew in years and beauty, the coldness which was gnawing at her mother’s heart, forever whispering evil rumours of the child, turned to a deep and abiding hatred. The queen had not troubled to make herself loved., neither by her husband nor by his people, and in all the country she had not a single friend. She was considered by many to be haughty, while in fact she was only a lonely and miserable woman. Her own beauty had soon faded, worried away by her evil temper and fractious, quarrelsome ways. She was thin and sharp as an evening shadow on the ground. Nobody loved her; nobody even liked her. They all doted on the blooming girl.

How the queen hated her! Every note of the child’s musical voice gave her pain, every graceful gesture cut her like a knife. You might think that, feeling this way, she would have sent the child out of her sight – but no such thing. She preferred to keep her always at her side, that she might torment her with barely concealed cruelty, and torment herself with the girl’s beauty. While the child’s father still lived she didn’t dare to show her hand too clearly, but when the Princess Hyacinthe was twelve years old the old king died. There was great mourning in the kingdom, for he had ruled wisely and well. The First Councillor took his place as Regent, until such time as the princess should be married. The little princess missed her father sorely, for they had been very fond of one another. She was frightened of her mother with the great, rapacious black eyes, the wheedling, whining voice, and the sharp, long-fingered hands that so often sought her arm with an insidious pressure that left blue marks on the white skin. Now that the king was dead there was nothing to stand between herself and the queen’s hatred.

Ever more beautiful, ever more graceful she grew, with a body like a young willow tree that bends in the wind, and the great, gentle eyes of a doe. Soon, too soon, thought the queen, the girl would marry and pass forever out of her power. By night the queen lay awake and plotted how she might hinder her beautiful daughter. Late, late into the night she lay in her bed of crimson silk, while the nightingales sang and the roses beneath her window perfumed the midnight air.

Every morning she left her restless bed to go to her daughter’s room. She must be the one to waken her in the morning, the first to draw back the bed-curtains and see the delicate girl breathing so softly under the silken coverlet, the first to see how much her beauty had increased overnight. On one such morning, a warm and rosy day in May, when all the birds were singing with even more than their accustomed gladness, the queen hurried, a little later than was her wont, to the princess’s bedroom. She had had a particularly troubled night – her sleep had been disturbed by confused, terrifying dreams. Swooping down the corridor in her black, feather-trimmed nightdress, she was like a bony bird of prey. Nervously, she dragged aside the silk bed-curtains that were glimmering in the morning light. Then, with a cry of horror, she fell down in a swoon upon the ground.

Her cry awoke the princess and brought the servants running. Hyacinthe sat up in bed, blinking with surprise. The servants came in and ran out again, screaming with fright. Wondering very much at this strange scene, the princess climbed down from the bed. She saw her mother lying on the ground. Gently, she raised her onto the bed and, in so doing, she caught sight of herself in the long mirror that hung upon the wall. With a strangled cry she sprang forward and peered at the image in the glass. A mask of hideously scarred and twisted flesh leered back at her where once had bloomed the sweet face of the Princess Hyacinthe. Only her gentle doe’s eyes were unchanged and, with speechless eloquence, bore witness to her plight. ‘Mother! Mother!’ she cried, sinking down on her knees beside the bed. ‘Why would you not love me, Mother! Look, oh look! and see what you have done!’ But the queen lay still in a swoon, and heard not a word of her daughter’s reproach. Snatching up a veil, the princess bound it tightly around her head and fled from the palace deep into the forest.

The Princess Hyacinthe ran fast and far, until she had quite lost her way. At last she grew hot and tired, and paused to rest. She followed the sound of water to a spring and, drawing aside the veil, stooped down to drink. While she was drinking a flock of sparrows came by and twittered to one another in their high, shrill voices: ‘Look what an ugly monster has come to live in the forest!’ They were frightened at the sight of her and flew away before she could offer a word of explanation. Later she gathered berries and apples for her supper, and sat down under a tree to enjoy her meal. But a flock of crows was sitting in the tree, and when she drew back her veil to eat they started up in alarm and cawed to one another in their grating voices: ‘Look! She is uglier even than we!’ And away they flew. The princess saw that not even the birds would come near her, so frightened was every living creature by her ugliness. She resolved that henceforth she must live alone. She built for herself a little hut of reeds, and there she lived on the gleanings of the forest, all alone, and no living thing came near her.

She had lived thus for a long time, and the warm days of summer were nearly ended, when one day a great white bear came to the little hut. He poked his head in the door and spoke to her.

‘Is that the Princess Hyacinthe?’ he inquired in his deep, gruff voice.

‘It is I and none other,’ she said, rising to welcome him. Her face was well hidden beneath the veil, which she never removed but to eat and drink. ‘Please come in, sir, if you can.’ You see the princess had not forgotten her manners, even though she was living all alone in the forest. The bear lumbered his way into the little hut, taking part of the door with him as he came.

‘I’m in need of a wife, Princess,’ said the bear. ‘Will you come with me and be my bride, and keep my house for me?’ The princess said that she would, for she was lonely there in the hut, and the bear had spoken kindly, although his voice was gruff. She climbed on his back and away they went, a three days’ journey through the forest, until they came to a dark cave where the bear had prepared a home for the two of them. ‘It’s only a cave, Princess,’ he said sadly, ‘but lest you find it cold and damp at night, you must lie down upon my back, and my fur will keep you warm and comfortable.’ And that is just what she did. Every night she lay in the bear’s embrace, and she was never cold or unhappy.

In the following year she gave birth to a little girl, and the child was very like the mother, white of skin, with raven hair and red lips, and a face as pretty as a flower. But she was like her father too, for she had bear’s eyes, great, black, and shining, and they called her Ursula which means little bear. It made the princess light of heart to see her lovely daughter. As the child grew in beauty every day, so the mother’s love for her ever increased. She could not bear the thought that any harm might come to the child. With her own hands she gathered rose petals to make her a soft bed, and plucked down from the wild swan’s breast to make her a warm coverlet. Ursula was a happy child, for she loved her life in the forest. She didn’t think it strange that her mother never uncovered her face, nor that her father was a bear, for what other life had she ever known? Her father took her for rides upon his back, that she might watch the treetops rushing by in the wavering sunlight, and the hares and smalldeer flying before their approach. She played with the sparrows and the bluebirds who came to sing for her, they even sat upon her little white hands and took a seed from her rosy lips. Sometimes she wondered if there weren’t other creatures like herself, though, for she saw there was a multitude of things in the forest, so many foxes and deer, and fish in the streams, and birds in the air. ‘Mother, am I the only little girl in the world?’ she asked one day.

‘No, you are not the only little girl. There are others like yourself, and little boys too, and men and women.’

‘What are they?’

‘Women are like myself. And men are also, but they are bigger and speak more deeply.’

‘Like father?’

‘Something like father, but they are not so large, and have not such a white fur coat.’

‘When may I see them, Mother?’

‘When you are older, my little Ursula.’` But now the child’s curiosity had been aroused, and she thought night and day of the others who were like herself, and often bothered and plagued her mother that she night go and see them.

Meanwhile the wicked queen had experienced a terrible remorse. She remembered all her wickedness towards her child with tormenting shame. She sent messengers in every direction, and tried for many years to trace the girl, but not a hair of her head was to be found. At last she came to believe that the princess must have been devoured by the wild beasts of the forest, and she gave herself up to grief. Three times a day she prostrated herself and cried bitter tears, but all her tears could not bring back her lovely daughter.

The Princess Hyacinthe had not forgotten her mother, and now that she had a little girl of her own, her thoughts turned often to the queen. ‘How lonely she must be,’ she thought,’ without a daughter to smooth her pillow when she is ill. And if she dies, who will lay her out and mourn beside her body, and weep at her grave? There are only the hirelings, and the ladies-in-waiting, and they are not fond of her.’ Thus she mused to herself, and her heart was smitten at the thought of the queen, growing old alone in a kingdom where she was not loved. But the princess did not dare go to her. At last she resolved to send little Ursula to spy upon the old queen, and see what manner of greeting she might receive.

She confided the plan to her husband, and he gave his consent. ‘She is your mother, after all,’ he said, in his gruff way. ‘It is only right that she should hear from you once in a way. I’ll take the child upon my back. That way she cannot come to any harm in the forest.’

You can imagine Ursula’s delight when she heard that she was to go on a journey to visit a strange queen. She could hardly contain her excitement, and trembled in every limb like a small tree in a storm. Her mother dressed her in her very best dress, that was woven of all the prettiest flowers of the forest; then she tied on her cloak of swan’s feathers and her little feather cap. The child’s face was very lovely, peeking out with her great bear’s eyes from the fluffy cap, and her mother kissed her again and again and cried bitterly, for they had never before been parted, not even for a single night. But the child was eager to be off, and did not cry. ‘I shall see you again in a week, Mother,’ she said, laughing. ‘Don’t cry, poor Mother! Father will look after me well.’ At last her mother gave her a basket of fine apples for the queen. Ursula climbed upon the white bear’s back and away they went into the forest.

At the end of a three day’s journey they came to the edge of the forest, beyond which lay the queen’s palace. The light of evening was just gilding the tall towers as they came into view, and Ursula clapped her hands and cried out, ‘Oh, Father, look! What is that lovely thing?’

‘That is the palace where the queen lives. You must go there in the morning and give her the apples. She will ask you many questions, but be careful how you answer her. When she asks you your name you must answer, Born to shame, I tell not my name. When she asks you where you come from you must answer, From the well of sorrow, from the bed of earthly woe/ From the loins of the white bear by his little doe. Then she will ask you who are your father and mother, and you must answer, Child of the flower, child of the bear/ My mother blossoms everywhere. Take care that you give no answers other than these.’ Ursula gave her word that she would do as her father had bidden her.

At dawn she made her way to the palace and sought admittance. She was delighted with everything she saw. To her eyes the footman seemed a most remarkable creature, and she marvelled at his purple livery with gold braid upon it, at his bright pink face and his white gloves, which she took to be his hands. All around her the maidservants were hurrying to their morning tasks, and she stared and stared at their dresses, their many shades of hair, their faces, each so different from the others. She saw that it was as her mother had said, the world was indeed full of people like herself, and it made her glad, but also afraid and shy, so that for a moment she forgot her mission and lost her tongue. She stood gazing about her at the brightly painted walls of the palace, the footman’s smiling face, the maids gathering in a ring around her.

‘What do you wish, little girl?’ said the footman.

‘To see the Queen, if you please, sir,’ she replied. At this they all laughed, and she was startled at the sound and blushed.

‘What a droll child,’ said the old housekeeper and put out her hand, not unkindly, to stroke the pretty feather bonnet. ‘Where do you come from, pretty?’

‘I may tell that only to the Queen,’ Ursula replied.

‘She is like the Princess Hyacinthe at that age,’ whispered the old footman, and the women hushed him and looked round fearfully, for it was forbidden to mention the name of the lost princess. ‘You may not see the Queen,’ he said aloud to the child, ‘but just leave your apples here and I’ll see that she gets ’em.’ At this little Ursula began to cry, not noisily, but discreetly; two big tears slid from her dark, luminous eyes over her lily-fresh cheeks, and the man was moved to pity. ‘Perhaps the Queen will be amused by this strange child,’ he thought, and he led her up the grand staircase to the royal bedchamber. He knocked and put his head inside the door. ‘A little girl to see you, Your Majesty,’ he said, and Ursula walked into the room.

The Queen was reclining upon her bed most augustly, and her thin, careworn face was not a pretty sight in the morning light. She frowned at the child and put out a hand as if to ward her off, but Ursula walked right up to the foot of the bed with her basket of apples. She fixed her great bear’s eyes upon the Queen’s face and stared so that the Queen began to laugh. She was much more agreeable-looking when she did that.

‘Come, child, what is your name?’ she said.

‘Born to shame, I tell not my name,’ said Ursula.

‘Tut, tut! A mystery is it? Well then, where do you come from?’

‘From the well of sorrow, from the bed of earthly woe,

From the loins of the white bear by his little doe.’ Thus answered the child.

‘The girl speaks in riddles,’ said the Queen to herself. ‘What a sweet face she has! She is nearly as beautiful as my Hyacinthe when she was such a little one as this. But her eyes are strange… I must find out more about this child.’ Aloud she said, ‘Tell me, my pretty poppet, who are your father and mother?’

‘Child of the flower, child of the bear,

My mother blossoms everywhere.’

‘Come closer, my dear,’ said the Queen. She took the child’s chin in her hand and looked long and carefully into her face, and Ursula looked back, wondering at the creases and furrows upon the skin, which were strange to her, at the sharp, darting, black eyes and the narrow mouth. ‘You are not pretty,’ the child thought, ‘but you are sad.’ And she was moved to sorrow by the sadness she saw in the old Queen’s gaze, and again two great tears rolled from her brimming eyes and down her cheeks. The Queen started and wiped them away with a gentle hand. ‘Why do you weep, child?’ she inquired. But the little girl only shook her head – she could answer no more questions. ‘Stay with me, child,’ said the Queen. I am a lonely old woman, stay and be my solace. I will make you my own daughter. You will live here in the finest palace in the world, and everything I have shall be yours.’ But the child only shook her head, and the Queen saw that she would not stay. Then she loaded up Ursula’s basket with silver and allowed her to depart.

Ursula returned to the forest and showed the white bear the silver that the Queen had given her, and related to him all that had come to pass. ‘You must return tomorrow,’ he said, ‘and again you must answer as you did today.’ He emptied the silver out upon the ground and filled the basket once more with apples, taking care that they should be red and ripe.

The next day Ursula again went to call at the palace, and this time she was shown immediately to the Queen’s chamber. Again the Queen questioned her as to her name and her origins, but the little girl answered in the same way as before. Again the Queen pleaded with the child to stay and again had to suffer her to depart. This time she filled the basket with coins of pure gold.

When the white bear saw the gold coins he sighed and poured them out upon the ground. ‘You must go again tomorrow, my daughter, ‘ he said sadly, ‘but this will be the last time.’

So at daybreak Ursula once more made her way to the Queen’s side. Again the same questions were asked and the same answers given, again she had to refuse the old Queen’s pleas. Then the Queen rose from her bed and took the child by the hand. She led her out into the garden where many beautiful flowers were growing. Their petals were all wet with the morning dew, their faces bright and fresh, their perfume sweet and mild. Ursula had never seen such a garden before, and everything delighted her. Drawn by the scent and colour, she ran to a bush of red roses and stood staring at them for all she was worth.

‘Do you like my flowers, child?’ said the Queen.

‘Oh yes, but I like these the best of all!’ said Ursula.

‘Then you shall have them,’ said the Queen, and she cut them with her own hands and filled the child’s basket with roses to overflowing. And as she cut them a thorn pricked her finger and she bled, and her blood lay like red dew upon the roses.

This time when Ursula returned to the forest the white bear gave a grunt of satisfaction. ‘Well done, little one,’ he said. ‘We may return home to your mother now. She will be fretting enough as it is.’ And swiftly as the wind they set off through the forest.

The Princess Hyacinthe was watching for them on the path, and ran to meet them , for they had been gone ten long days and she had nearly given them up for lost. She took the child in her arms and lay her face upon the soft fur of the white bear’s neck, weeping for joy. They went together into the cave, and there she heard all that had befallen them. But when she beheld the basket of flowers she thrust them aside and began to weep afresh. ‘Ugh, they are blood roses,’ she said. ‘What thinks my mother to send such a gift?’ Then the white bear rebuked her. ‘You must take the gift in the spirit in which it is given, for the Queen has watered them with her tears,’ he said. So Hyacinthe filled a pitcher with water and set the roses there, that they might yet live a little while. And as she placed the flowers in the pitcher the droplets of blood splashed down onto her hands. Again she cried out in disgust, ‘Only look what my mother has sent me!’ She wiped the blood from her hands with a napkin and threw it on the floor in her vexation. Again the white bear rebuked her. ‘Wife, don’t be a fool! You must take the gift even in the spirit in which it is given.’

That night, when the princess was well asleep, the white bear retrieved the napkin and slipped it under her pillow so quickly, so cunningly, that she knew nothing of what he had done. But her dreams that night were strange and sad. She awoke very early, when it was still dark, and pulled the bear’s ears to wake him.

‘Husband, I have had such a dream!’ she said, by way of explanation. ‘I dreamt I was a beauty once again, and felt the wind blow fresh upon my cheeks.’ And at this she sighed, for she knew that it could never be.

‘Why not remove the veil and see if it isn’t true?’ said the white bear. But the princess only sighed the louder and shook her head.

‘Ah no, for if once you saw my face you would never love me any more. No creature can bear to see it; it is too terrible, and I could not bear to lose you.’

‘Now listen to me and do as I say,’ said the bear. ‘There’s a full moon tonight. Go out to the spring yonder. There you can remove your veil and see if anything unusual has come to pass.’ The princess trusted him so that, although she was most unwilling, out she went into the night.

It was the time of year when winter is fast approaching ,and while they had been sleeping the first snow had fallen. The moon and the stars were shining upon the whitened trees; they glittered and glimmered as if a thousand diamonds grew upon their branches. The Princess Hyacinthe came to the place where the flow of the spring was slowed by the rocks to form a little pool. This pool had frozen in the cold and was now as smooth and clear as any mirror. With a beating heart she removed her veil and bent over the glassy ice.

By the light of the moon she saw at once that all her beauty had been restored to her, and more besides. For where once there had been sweet, youthful freshness there was now wisdom as well, and where once there had been only thoughts of self, there was now love for others. What was once a bud was now a flower, and she was Hyacinthe indeed.

She knelt for a long time in the snow, nor did she feel the cold any longer. She thought of all the years in the forest, of all that she had learned from husband and child, and she thought of her mother, whose lonely heart she could now assuage. Her own heart was full to bursting, so that she could neither move nor speak. But she was startled from her reverie by the sound of footsteps in the snow. She whirled round and saw a man approaching her, arms outstretched. At this she was afraid, for no man had ever been seen in that part of the forest, and she thought he must mean to do her harm. Caught at the edge of the spring, she was unable to flee, but only watched as he drew closer and closer. His hair was as white as snow, but his face was young and handsome, and when he was nearly upon her she saw that his eyes were dark, luminous, and gentle. ‘Don’t you know me, Princess?’ he asked, and at that instant she recognized the white bear and fell into his arms.

He carried her back to the cave, and there he told her of how he had long loved her, and had sought her hand in marriage but had been repulsed by the old Queen. He had followed her into the forest at the time of her misfortune, and had changed himself into a bear in order that he might watch over her during her trial. But now that she had forgiven her mother, he was free to resume his own shape. Only his hair must remain white as a token of all he had endured.

When the day had well and truly dawned, they set out with little Ursula for the Queen’s palace. You can imagine with what rejoicing they were received there. Of course there was a scene! Of course the Princess Hyacinthe and the old Queen fell weeping into one another’s arms and vowed never to be parted again, nor were they in this life. But it was Ursula whom the old Queen loved best, and the two of them spent many happy hours together playing in the garden and climbing up and down the steep towers of the palace. It was wonderful to see how the old lady could still run about after the child, for she followed her as if she were her shadow, and had her to sleep in her own room at night. In time her face became quite pleasant and pink, as the lines of care were replaced by those of laughter.

He that had been the white bear became king over all the kingdom, and he must have ruled wisely and well, for he was called Good King Ursus by his people. And although he was a fair and just ruler, it is said that the one fault he could not abide was envy, and that any man or woman so accused was banished from the kingdom forever, condemned to wander in the dark forest, to weep and gnash his teeth in the wilderness, until such time as He shall come who is to be Judge over us all.

Grace Andreacchi is an American-born novelist, poet and playwright. Works include the novels Scarabocchio and Poetry and Fear, Music for Glass Orchestra (Serpent’s Tail), Give My Heart Ease (New American Writing Award) and the chapbook Elysian Sonnets. Her work appears in Horizon Review, Eclectica, Word Riot and many other fine places. Grace is also managing editor at Andromache Books and writes a regular literary blog, Amazing Grace. She lives in London.

Author’s website: http://graceandreacchi.com

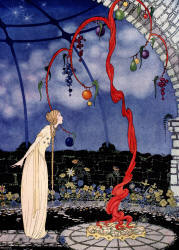

Image: From Old French Fairy Tales, Virginia Sterrett, 1920.