By Carolyn Turgeon.

Mermaid, which just came out in March, is my third novel and second based on a classic fairy tale. My last book, Godmother, imagined the “real” story of Cinderella’s fairy godmother… It was a tricky book to write, but the moment I put myself in the head of the godmother, and of Cinderella herself, I knew that my own book would take a darker, and to my mind more psychologically accurate, turn. Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” on the other hand, is very odd little story, full of suffering and pain and heartbreak already. At first it seemed entirely inaccessible, too weird and sad for a retelling. But then I thought about that mysterious princess who takes up only a few lines in the story but is the one the prince loves and ends up marrying’”and in so doing, breaks the mermaid’s heart and causes her to turn to foam’”and I thought that there might be something there to explore.

Mermaid, which just came out in March, is my third novel and second based on a classic fairy tale. My last book, Godmother, imagined the “real” story of Cinderella’s fairy godmother… It was a tricky book to write, but the moment I put myself in the head of the godmother, and of Cinderella herself, I knew that my own book would take a darker, and to my mind more psychologically accurate, turn. Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” on the other hand, is very odd little story, full of suffering and pain and heartbreak already. At first it seemed entirely inaccessible, too weird and sad for a retelling. But then I thought about that mysterious princess who takes up only a few lines in the story but is the one the prince loves and ends up marrying’”and in so doing, breaks the mermaid’s heart and causes her to turn to foam’”and I thought that there might be something there to explore.

So the book I ended up writing tells the story of this princess. And, since it seemed a shame to tell a mermaid story and not include the mermaid, I told her story, too, alternating between the two tales, and ended up making the book more about the relationship between these two romantic rivals than about anything else’¦ In my version, the women both love the prince but have much more at stake than their own hearts, when it comes down to it. Once the story is set in motion and both women have made their sacrifices, leaving their homes behind to gain the prince’s heart and hand, they both have too much to lose. If the princess doesn’t marry the prince, her kingdom will stay divided and at war. If the mermaid doesn’t, she’ll turn to foam. When they discover each other at the castle, and realize that they have unwittingly become rivals, we know that the story cannot end well.

For the year or so I spent writing the book, I half-lived in Hans Christian Andersen’s story. I wanted to imagine the princess’s story as fully as possible while remaining true, to whatever extent I could, to the few details about her in the original tale. And with the mermaid, I wanted to stay true to some of the story’s main moments, to give the reader that feeling of recognition and pleasure. I wanted to tell the story as it “really happened,” the idea being that Hans’ version is how it was passed down centuries later. And so I read the story again and again, and I let its world and images populate my own imagination.

Unlike “Cinderella”, which can be traced back to multiple sources and has been retold numerous times and in many classic renditions, “The Little Mermaid” is its own singular creation, and the truth was I wasn’t too familiar with Hans Christian Andersen outside of his few most famous stories. And so once my book was done, I wondered about this man who’d spun such a sad, luminous tale, and to whom I owed so much imaginative space, and such a debt.

So I decided to learn something about him, and to make a pilgrimage of sorts to the country he came from.

I finished the last edits of Mermaid in the spring of 2010. That August I found myself in Berlin, Germany, for some months, so it was easy enough to plan a whirlwind trip to Denmark, especially with the low-budget help of EasyJet and Kayak. In the meantime I picked up two huge biographies of Hans as well as his collected stories at the English bookstore in Prenzlauer Berg.

Though I learned all kinds of other details about Hans’ very strange, singular, over-the-top life, I couldn’t help but see him, and the places I visited, through the lens of this heartbreak and longing, not to mention an extreme theatricality and love of drama, which I can absolutely appreciate and secretly suspect were in keeping with my own sensibilities…

My visit to Denmark was a quick one, with no time for dawdling. I flew in and out of Copenhagen, stayed at a cheap hotel next to the train station, and spent one evening walking around Copenhagen, another whole day travelling to Odense, and one half day walking around Copenhagen before flying back to Berlin. I’d done a similar thing for Dante in Florence, armed with a sense of what things had been before, exploring the city and determined to kind of see past the modern buildings, cars, streets’¦ and into a past that was in evidence all around you. It’s a strange way to explore the city, squinting, trying to imagine what it was like once, trying to sense the presence of the ghosts and memories that haunt its streets and buildings. And Hans was a restless sort, so he lived in multiple places through the years, which was rather inconsiderate of him and gave me a long list of places to visit.

I also was determined to film everything. And I have to tell you: Danish people think it’s weird when you stand on the street pointing a Flip camera at yourself and speaking in English, and will actually stop and smile at you and occasionally wave. New Yorkers they are not.

So aside from the non-New-York-ness of it all, the first and main thing I noticed about Denmark was the absolute aggressive healthfulness of everyone around me. Those Danes are all super fit, whizzing past you on bikes and gleaming with health and just generally being obnoxious. The second thing I noticed is how much Hans Christian Andersen’s life is woven through Copenhagen and Odense, sometimes garishly, sometimes in just the barest traces. Plaques and street names are all over the place, statues of him gazing out in mournful, lonesome fashion, even as adoring, camera-wielding crowds surround him. The third thing I noticed is that they really, really like 7-11. But I digress.

From the Copenhagen airport I took the train into the city, and my hotel was just a block away from the main station. I checked in, then walked over to Tivoli Gardens, which was one of Hans’ favorite spots and also conveniently located within a couple blocks of the train station and hotel. Tivoli is the world’s second oldest amusement park (it opened in 1843) and a huge attraction, though you wouldn’t exactly know it on a rainy September weekday afternoon, when it was almost entirely empty. But I tried to imagine how wondrous it would have been in the mid-19th century (not to mention on a lovely summer day now, filled with people), as I walked along its many pathways lined by flowers and fountains and elaborate Oriental-style buildings with giant peacocks and the like flaring out of them. There’s a lake, there are open-air restaurants and cafes, and though the park has evolved in the last 160 years or so it was, from the start, filled with mechanical rides and this lush exoticism that Andersen loved, and that inspired his Nightingale fairytale.

Next I visited City Hall, which is right across the street from Tivoli and which features, right on the sidewalk, a huge statue of Hans Christian Andersen.

The statue made me very sad that I wasn’t there with someone so that I could climb in said statue’s lap and pretend to make out with it, or read over its shoulder as I would later do in Central Park, which has its own gloomy statue.

But still it is something, seeing that mournful face staring up at Tivoli, an image of that lonely, sad and wonderful man, who spun such heartbreaking stories, frozen in stone next to the imposing City Hall, which is fronted by fountains and some looking-like-they’re-about-to-launch-themselves-into-the-air gargoyles.

For weirdness, though, the Wonderful World of Hans Christian Andersen (http://www.topattractions.dk/) was definitely at the front of the pack. I was expecting a bona fide museum’¦. and instead found a series of weird tableaux from Hans’ life as well as his stories, which you can have told to you in several languages as you watch scenes from them mechanically acted out. I thought the little mermaid display was especially strange, with its mermaid gazing up longingly at an impossibly phallic, out-of-reach castle with a prince’s head popping out of it.

Slightly traumatized, and with night approaching, I retired elegantly to my room to prepare myself for an early morning train ride to Odense, which is a 90-minute ride away from Copenhagen and the town Hans is from. Plus Odense is located on the poetical-sounding “Fynn Island” and is where Hans retreated to write “The Little Mermaid” when Edvard was getting married, so I was expecting something a bit more magical’¦ not a big shop-filled train station with about 50000000000000000000 bicycles parked in front. Which is what I found there after a lovely night’s sleep and after nearly missing my train by setting a loud alarm on my laptop and then accidentally leaving earphones hooked into it. But once I recovered from my mad dash and the modern world generally, I started walking toward the Hans Christian Andersen museum, which was built around the small house in which he was born, and saw that Odense is really very charming, despite its many mad, murderous bicyclists.

There were several photographs of Hans about, which made me wonder why he was considered so deeply unattractive by his peers. And he was: this is confirmed again and again. Edvard Collin is there, and appeared to me a rather hunky sort, too.

What I most loved at the museum, though, was the basement full of curiosities illustrating how truly weird Hans Christian Andersen really was. For example, he was so afraid of fire that he carried a rope with him everywhere so he could make a quick escape should the need present itself’¦ and there in the museum is the actual rope. You see shaving implements that Hans’ barber used on him’¦ and learn that Hans’ nose was so big and he moved around so much that his barber actually had to hold onto Hans’ nose in order to give him a shave. THIS is the kind of thing one longs to know about one’s literary idols, let’s face it, and I ended up spending hours in the place.

Odense is a really lovely little town, I have to say. From the museum you can walk down these cobblestone-y streets lined by quaint old houses with pointed roofs, down to the river that snakes through the town and is lined by trees and grass. I kept imagining a moony Hans hanging out at this river, looking down at his reflection with that sad sad face, imagining a little mermaid longing to be part of the world of humans. I wandered along the river, under a bridge covered with graffiti, and along this pretty pathway that leads to a big statue of Hans right smack in the middle of a park, all green grass and loveliness and picturesque bridges and churches, and he’s standing alone there, ever mournful, so I sat for a long time and took photos and watched joggers and lovers zoom past.

And then I wandered around to the house where Hans grew up, which is past the river and the park, and down a street or two… It’s quite a small house set up as if Hans’ family had just left it, with Hans’ cobbler father’s work set out on a table, and pans hanging in the kitchen. Much is made of Hans’ poor, simple upbringing and his longing for the finer things, and I can imagine how much Hans did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps. Actually, the whole set-up made me think of Dolly Parton, whom I love, and who has explained her own over-the-top, theatrical tastes as being a result of her mountain childhood. To me Hans seems just like that, coming from this humble place, moving to the big city and going overboard in his quest for elegance and beauty in a way that might make your bluer blooded folk a bit uneasy.

After, I went to a quaint café for some coffee, and just wandered around the town until it was time to catch my train back that evening to Copenhagen. I passed the fancy-looking Odense Theater, where a show was about to start and people in fine dress swarmed around out front, just as the sun was setting, and wondered if it was there when Hans was a boy, to help spark his many longings.

I returned to Copenhagen that evening, and the next day, my final day in Denmark, I had until mid-afternoon in Copenhagen to hit the list of other Hans Christian Andersen sites I’d accumulated, including almost all his former residences in that town. The strangest of these is located in Magasin, which is a regular department store, like Saks or Bloomingdale’s, housed in what once was a grand old hotel. Once upon a time, Hans rented two attic rooms in this hotel, and up until recently these rooms were preserved and accessible to visitors from Magasin’s third floor. Sadly, the shop ladies told me that the exhibit had been recently shut down, but I went back and found the remnants of it, right behind the cappuccino makers and fancy knives. I took out my Flip camera and brazenly walked back into the little hallway (still filled with images of Hans) that led to what I presume were those rooms and that now seemed to be filled with artisans of some kind, and I continued to film this weird, incongruous place until a lady came and kicked me out.

I then made my way to the nearby Royal Danish Theater, which Hans desperately wanted to join when he left his humble home and flung himself into glamorous Copenhagen at age 14. There are crazy stories of the precocious boy foisting himself on the theater’s director (who told him to go learn a real trade) and then showing up at the home of the theater’s prima ballerina and astonishing her with a madcap on-the-spot audition that left her equally charmed and horrified.

I tried to find the spot where this ballerina lived and where Hans created such a spectacular scene, but now it’s a street full of shops and I had little luck. And I admired the theater itself, although it’s not the same building Hans frequented (and eventually did end up doing a lot of work for, in a fringe-y kind of way). But I visited Hans former ambitions in spirit, anyway.

Then I headed to famous Nyhavn, a harbor street split by a canal that’s filled with picturesque boats and lined by open-air cafes and bars. Hans lived in three spots on this street: at number 20 he wrote his first fairytales in 1835, at number 67 he lived from 1845 until 1864, and at number 18 he lived from 1873 until his death two years later. These are all just regular residences now, with only small plaques on the facades to tell you who once lived inside.

I wondered if the people inside, who actually live in these old haunts, care about this history, or if they’re just so used to it, and to Hans’ ghostly presence generally, that it seems normal. It’s a beautiful street, though, and I imagined it was when Hans lived there, too.

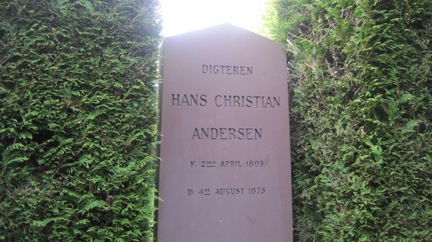

Finally, I visited the cemetery where Hans is buried, the Assistens KirkegÃ¥rd, which I braved the metro system to visit. From what I could tell it seemed like a large cemetery, and I was afraid I’d get lost in some weird Gothic labyrinth and possibly attacked by ghosts. As it turned out, the moment you walk in there are about 5000 signs to point you to Hans’ grave, which is maybe a one-minute walk from the front gate. (Kierkegaard is also buried there, but I didn’t see any signs to his final resting place.)

I was hoping to film a book trailer at Hans’ grave, though I’ll admit it was a bit Goth-y of me, especially as I was dressed all in black’¦ but this proved to be quite difficult since apparently Danes like to just hang out and jog and take romantical walks through cemeteries, and on top of that Hans’ grave itself is massively popular, even on a weekday afternoon, it seems. Every time I started to film something another pair of lovebirds, or group of schoolchildren, or lone jogger, or bevy of stroller-pushing mamas, came by. Apparently in the summertime the Danes have picnics and sunbathe amongst the dead, too. Maybe when your most famous dead person is a sad-faced oversized man who wrote devastating stories of mermaids turning to foam, you’re a little less glum about death generally? But I sat in front of his grave and did my best, and thought it a blessing that my lack of understanding Danish likely spared me many impolite observations of my person.

And then I was out of time, which is an appropriate thing to be whilst sitting in a graveyard, and so I hightailed it back to the subway, and to my hotel, and to the train station and the airport, and back to Berlin.

All in all, I’m not sure how much insight I got into Hans Christian Andersen through this visit to Denmark, but at least occasionally, when I squinted, I felt like I had some sense of the world Hans lived in, with its magical amusement parks and tree-lined rivers and grand theaters, its tiny apartments, its cobbled streets and gloomy skies. How much of this was in my mind and how much in the world itself I don’t know, but I’m not sure that my new best friend Hans would have cared too much about the distinction, anyway.