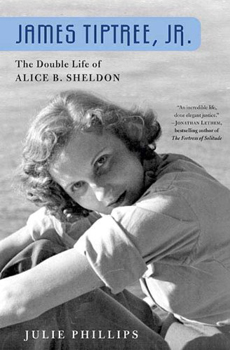

James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon

By Julie Phillips, 2006

Reviewed by Tanya B. Avakian

Before she died, James Tiptree, Jr. was a secret shared between a few obsessed readers. Many of us were pointed in her direction’”she was a woman by then’”after reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s introduction to Tiptree’s short story collection, Star Songs of an Old Primate. Those who went on to read Tiptree’s stories may also have learned more about her by chasing down the interviews she gave once her identity was revealed. Tiptree was born Alice Bradley in 1915, the only child of conspicuously wealthy, talented, and eccentric parents. Her mother, Mary Hastings Bradley, was a socialite and a celebrated writer of detective stories, who comes across somewhat as a Mrs. Jellyby in Julie Phillips’ outstanding biography of Tiptree. She was progressive for her time and concerned to a great degree with human and animal suffering. According to her friends, Bradley spoke in “monologues” and had great powers of persuasion, with rather less ability to listen. She took Alice with her to Africa despite the protests of horrified friends, convinced that she was doing Alice a favor by showing her the last unspoiled continent in the nick of time. Big game hunter Carl Akeley, with whom the Bradleys were traveling to study mountain gorillas, also liked the idea: “He wanted Alice to be the witness to an Africa of peace and beauty, the lamb sent to lie down with a gentle lion, and hoped that Africa ‘˜seen through the eyes of a sweet little girl’ would be ‘˜all the more beautiful than when seen through the eyes of rather blood-thirsty sportsmen and adventurers.'”

Before she died, James Tiptree, Jr. was a secret shared between a few obsessed readers. Many of us were pointed in her direction’”she was a woman by then’”after reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s introduction to Tiptree’s short story collection, Star Songs of an Old Primate. Those who went on to read Tiptree’s stories may also have learned more about her by chasing down the interviews she gave once her identity was revealed. Tiptree was born Alice Bradley in 1915, the only child of conspicuously wealthy, talented, and eccentric parents. Her mother, Mary Hastings Bradley, was a socialite and a celebrated writer of detective stories, who comes across somewhat as a Mrs. Jellyby in Julie Phillips’ outstanding biography of Tiptree. She was progressive for her time and concerned to a great degree with human and animal suffering. According to her friends, Bradley spoke in “monologues” and had great powers of persuasion, with rather less ability to listen. She took Alice with her to Africa despite the protests of horrified friends, convinced that she was doing Alice a favor by showing her the last unspoiled continent in the nick of time. Big game hunter Carl Akeley, with whom the Bradleys were traveling to study mountain gorillas, also liked the idea: “He wanted Alice to be the witness to an Africa of peace and beauty, the lamb sent to lie down with a gentle lion, and hoped that Africa ‘˜seen through the eyes of a sweet little girl’ would be ‘˜all the more beautiful than when seen through the eyes of rather blood-thirsty sportsmen and adventurers.'”

Alice was six when she went to Africa for the first time. She was eight when she went the second time, and saw natives crucified on crude wooden posts, swarming with flies and ants. She was fifteen on the last visit, when she and her family were nearly left to die in the desert by Belgian Congo officials because, she believed, they knew too much about Belgian prison camps for natives. To outsiders, Alice appeared to relish these adventures. It was only later that she would reveal how excruciating they were, made more so by her status as a little white girl. “It was early impressed on me that I was viable only within the sheltering adult group, that the outside was dangerous and beyond my strength… I never was allowed to learn to combat it; I lived helplessly inside, watching, learning the adult lore, wondering how I could meet each horrible challenge, and never getting a chance to practice.” She especially resented never being allowed to fire a gun. At the same time, the blonde little girl was led to think she was special in the way of the young Lord Greystoke. When in her fifties she was still trying to individuate, Alice Sheldon reflected that the only model of female identity available to her was the deadly one of this child. “I think you could say that one of my hobbies is recovery from the status of Marginal Man’”with no place to recover to except being my parents’ dear little yellow-haired darling with its head full of Death.” As if to seal the bell jar of race, class and femaleness, all defined as eternal childhood, Mary immortalized her daughter in two picture books, Alice in Jungleland and Alice in Elephantland. When the Alice of those books asks about slavery, Mary responds: “It was too big a problem for a six-year-old to worry over, so Alice’s mother soon started her talking of something else.” In a few more years, Alice would spend nights at her Swiss boarding school walking the railroad tracks in the hope that a train might hit her. In her words, her African experience left her with “a case of horror vitae that lasted all my life.” It also left her with no peers among a generation of conventionally reared boys and girls. Mary Bradley overcompensated for the way she had brought Alice up by demanding that the spoiled and traumatized girl conform to the age’s strictest standards of femininity. Worse still, Alice’s loving but distant father had always wanted a boy.

Alice Bradley grew up brilliant and miserable, with a starlet’s looks, the mind of a genius, and an early sense of the world as beyond saving and herself as doomed to tragedy. She suffered from bipolar depression, most probably from birth. Everything indicated that if she followed up on early promise and became a writer, it would be in the mold of her contemporary Jean Stafford. She was a Sarah Lawrence dropout. She was groomed as a society beauty, to follow in her mother’s footsteps. Instead, at nineteen, she used her debutante party as the occasion to elope with another rich waif, Bill Davey, and spent the next decade in a fashion more appropriate to the Jazz Age than the period of the Depression and Hitler’s ascendancy. (If she escaped Stafford’s fate of having her face bashed in by a car wreck with a drunken poet at the wheel, it was not by the Daveys’ design.) Then the war began, Alice Davey divorced, and found a niche of sorts as a WAAC in photo intelligence. She married her commanding officer in the CIA, Col. Huntington “Ting” Sheldon, a decade older and also divorced. After the war she lived as a housewife with numerous dilettante pursuits. Her marriage was sexually unfulfilled but otherwise happy, after a rocky start. She wanted children, but had been sterilized by a botched abortion in the thirties. Sheldon eventually settled in McLean, Virginia, with Ting, and got a doctorate in research psychology. Like most of what she did, it was done very well and she could not see it leading to more than a hobby. She claimed that the sexism she had already encountered in the field made a professional career unappealing to her. The truth was that she was also loath to pursue grantsmanship. In her own way she was as egotistical as Mary Bradley, though she would always lack her mother’s confidence.

In 1967, fresh from finishing her doctorate, Alice Hastings Bradley Davey Sheldon found a new hobby and a new identity. She persisted for years in the fiction that she decided to call herself “James Tiptree, Jr.” because she would never be taken seriously as a research scientist if anyone knew she wrote science fiction. She might have appealed to the genre’s distinguished history in world literature, particularly that which dealt with the themes of love and death. But while science fiction writers and fans are justified in wanting our voices to be taken seriously, kicking against the prevalent stereotype of the genre as being concerned with “talking squids in space,” in Tiptree’s case the talking squids and chain-mail bikinis are entirely apropos. Sheldon needed to write junk, as she saw it, in order to write at all. She included virtually every cliché that’s caused science fiction to be written off as junk and did so with glee; her first novel, Up the Walls of the World, even had talking squids in space, to adapt that unfortunate comment on the genre as junk by someone who should know better, Margaret Atwood. The irony is that if any genre fiction author were anointed to address Margaret Atwood as a peer, at the least, in seriousness, it would have to be Tiptree. Her true subject was pain. She made Atwood look sentimental, fooling the reader again and again into taking a story as a lark, a Captain-Kirk romp, and ending it with a finale drawn from Sheldon’s bloodiest memories of Africa. In one tale, “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain,” her hero saves the Earth by killing off humanity with an epidemic. In another, “On the Last Afternoon,” she quoted Robinson Jeffers: “Be in nothing so moderate as love of man.” That story took the sci-fi plot of a lone hero defending a space colony against giant lobsters and added Sophoclean detail: the lobsters are menacing the colony because it is their breeding ground and the spacegoers have foolishly staked their territory on it; the hero is offered an escape from his fate of dying to protect the colony, and does not take it, with Jeffers’ line and the story’s conclusion to remind us that his sacrifice is both futile and a little suspect. “Her Smoke Rose Up Forever” posits the thesis that the most profound torment continues to exist as wayfaring tatters of consciousness in the cosmos: “atrocity without end or comfort, forever.”

The stories’ cruelty was stunning. So was their verbal brilliance, putting readers in a difficult position. Stories that asked the same questions as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Arthur Koestler, Tadeusz Borowski and Andrea Dworkin, also dallied with cuteness by definition. The genre that gave them their lyric compression lent itself to the danger of condescending to the reader or, worse, to Sheldon’s own voice. Sometimes they collapsed into pat sociobiological recipes for despair; more often, they did not, though their concision gave their pessimism a hermetic seal. She was especially pessimistic about the prospects for the women’s movement. “The women’s movement is dependent on the civilized acceptance of men… [Feminists are] a little’”a little’”like a beautiful deer in a game park where they have temporarily suspended hunting season. There are few such parks and god knows how long this will last.” In “The Women Men Don’t See,” she asserted through one of her characters that “The women’s movement is doomed… Women have no rights… except what men allow us. Men are more aggressive and powerful, and they run the world. When the next real crisis upsets them… we’ll be back where we always were’”property.” The woman who utters these sentiments in the story chooses to go into outer space with the aliens rather than remain under the protection of the classical male space-opera hero. Of course, the reader who was upset by all this could take comfort in the fact that Sheldon had no hope for the rest of the world either.

The author of this review sent her a fan letter early in 1987, and received a brief note in response that included a promise to write more later. Approximately a month thereafter, a news item appeared misspelling Alice Sheldon’s name as “Shelden” and announcing that she had shot her husband and herself. The news story appeared just a few weeks after the death of Primo Levi, also a suicide and also a science fiction writer, under the pseudonym of “Damian Malabaila.” In both cases the death was not only sad, but unspeakably disturbing when read in conjunction to the work. While the suicide was not unlike that of other elderly couples’”Ting Sheldon was blind and bedridden, with some form of dementia; Alice Sheldon, a chain-smoker, was suffering more and more from heart disease as well as from depression’”Sheldon/Tiptree had written much about suicide and more about despair, creating the likelihood that her work would now be written off. It was all the more ironic in that almost nobody could see it coming. Le Guin observed: “I think a lot of us didn’t realize how bleak her stories are until the end, when we saw that she really meant it.” By 1987 Le Guin was grappling with her own despair, “the Dark Hard Place,” in which she was abandoning her earlier allegiance to the conventions of science fiction (including male protagonists) to write self-consciously in a mode that we might now call ecofeminist, but was then very new. She was also convinced that by having written fiction set in a technological future, she was complicit in the destruction of nature and domination over women and people of color. Ironically, Tiptree had always encouraged Le Guin to write more dystopian fiction in the style of “The New Atlantis” and The Lathe of Heaven, both of which Tiptree greatly admired. Now Le Guin was at the head of a backlash against science within the core of feminist science fiction. “Eye in the telescope/looks back, can’t see hope,” Le Guin wrote in a poem she submitted as her autobiographical statement to The Faces of Science Fiction. If science fiction was oppressive by definition, space opera was beyond the pale. All this was the setting in which Sheldon was guaranteed to be disappeared by the brutality of her death and the uncomfortable questions she raised about a genre that was supposed to assure us of a future.

One of the many wonderful things about Julie Phillips’ biography of Sheldon/Tiptree is that she does as much as anyone can to lift the burden left by Sheldon’s suicide and release us to delve back into Tiptree. It is now 2010, and the fate of the world is outstripping many of her worst imaginings, but for that very reason some of Sheldon/Tiptree’s stringencies may now say more about her than the rest of us. Most specifically, many of her stated ideas about men and women can seem to be far off the mark, based on Sheldon’s confusion over her own gender identity rather than a clever subversion of it. In some ways her biography invokes every hackneyed psychoanalytic argument against feminism, and Phillips is brave indeed’”as Tiptree was’”to take the risk of incurring these arguments. Sheldon resented her mother, would have preferred to be a man, was frustrated in her desire for motherhood, and above all, tortured over her sexuality. Sheldon kept a file on “Dead Birds,” as she called her platonic attachments to women; all ended in heartbreak, in one case with the woman dying almost literally in Sheldon’s arms. Apart from brain chemistry and posttraumatic stress, this now appears the most logical source for Sheldon’s anguish. Sheldon never fully accepted her lesbianism even in theory, in part because it was impossible for her to reconcile love for women with what she knew of women as sexual objects for men. Her desire for women was inseparable from her male identification. In the first part of her century she might have gotten away with this by taking on the role of a trouser dyke, like Katharine Hepburn in “Sylvia Scarlett,” but not in the age of lesbian feminism. Morally suspect as male sexuality was for Sheldon as a model, it was also impractical: by the time she was writing there was no more unequivocal way to declare oneself a woman than to admit to being gay. Sheldon learned as much in a typically painful and ironic way, through the confidences of feminists who thought she was a man. A seminal author of feminist science fiction, Joanna Russ, who was one of Sheldon’s closest and most honest correspondents, appears first to have identified herself as a lesbian in her letters to Tiptree. After Sheldon herself came out as a woman, Russ proposed they become lovers, how seriously we cannot know. Sheldon excused herself as being too old.

With these revelations, it becomes a lot easier to decipher some of the alarming sexual politics that play themselves out in the author’s analyses of her own work. Sheldon was convinced that any true feminist movement was doomed by the nonviolent nature of women. Human cruelty and violence being her own great theme, she was thus driven to despair by the thought that nobody would take her insights seriously if they knew her identity. As a woman, she could be a witness to pain but she could not fire the gun. It didn’t matter that her own longing for violence provided her with her raw material, even if it was mostly self-directed. Least of all could she write from her sense of being an outside observer of the female condition, with as much contempt for women as admiration. Both derived from her conviction that women were too good for the world, or should be. This conservatism is reflected in “Houston, Houston, Do You Read,” where the only tenable cure for women’s oppression is to create a world without men. Other radical feminists were saying similar things, and being challenged by still other feminists for their essentialism. But so long as she was a man, Sheldon could take her sexism to its logical conclusions and achieve inspired subversions of male chauvinist stupidity by demonstrating, in effect, what would happen if women really fell for this gender stuff’”they’d have to flee to another planet or, failing that, remake this one. Having been flushed out as a woman, Sheldon stopped writing stories like “The Women Men Don’t See” and “Houston, Houston, Do You Read,” and restricted her feminism to variations on the theme of ineffectual nonviolence versus the seduction and hopelessness of violent power, more ethical allegory than science fiction.

Phillips’ gentle but relentless disentangling of Sheldon’s gender trouble does much to explain this shift, as it does Sheldon’s own deterioration when she was unmasked and had little choice but to be a feminist author for real. The story of Sheldon’s unmasking and final decline is complicated. It passed the point of no return when Mary Bradley died and science-fiction fans recognized her biography in obituaries from Tiptree’s letters, next noting that her only survivor was a daughter rather than a son. As indicated, the end had begun a few years earlier when Tiptree became an active participant in science fiction’s feminist community. As a sensitive male writing openly on feminist issues through the sexist clichés of science fiction, and warmly available to “his” many correspondents, Tiptree was besieged by the new feminist writers of the 1970s. Joanna Russ and Ursula K. Le Guin attacked each other through “him” and were defended to each other by Tiptree, who was close to both. Le Guin was alarmed to find that Tiptree was virtually unstrung when “he” became the target of feminist anger: one did not expect a man to be so troubled by it. Le Guin never guessed that Tiptree was a woman, but she did think he might be crazy, and worried. Yet she, like Russ, was impatient with his refusal to come clean on certain points of great importance to feminists, such as his own sexuality (was he gay?). And no matter how Tiptree placed himself on the feminist grid, he could not please anyone forever regarding the very questions that had tormented Sheldon all her life: What was female nature? Was it a prison? Were the restrictions on women an expression of biological or social structure? If the former, or the latter, were true, was it hopeless to seek change? How far did one need to go? Sheldon was used to being alone with these questions, and was frightened, not liberated, when she found they mattered as much to other women writing science fiction.

Tiptree’s identity was the subject of much speculation among science-fiction fans well before he became especially conspicuous as a feminist. Sheldon had not helped matters by intimating that Tiptree could not reveal himself because he worked for the CIA, when her own brief stint for the CIA was thirty years in the past. Much of Tiptree’s mystique arose from this legend, and it bears some commentary. The feminist connotations are tempting: in “The Women Men Don’t See” Tiptree had already intimated that all women are spies in alien territory. Nor was Alice Sheldon above being titillated by the mystique of the female spy in popular culture. But her male identification is also plain to see in the “CIA spook” cover that was her only outright fabrication in the persona of Tiptree, apart from his gender. Tiptree was nicknamed “Tip,” similar to Ting. It was more than a trick of fusing with her husband in a manner at once faithful and competitive, getting some of the respect for her own adventures that he had as a high-ranking CIA official throughout the fifties; it was a way of admitting that the world of McLean was one into which she fit. William Gibson, author of Neuromancer, grew up in this culture and recalled that the children of CIA functionaries were especially vulnerable to “epidemic drinking, depression, drug-abuse, auto accidents, suicides.” Sheldon could not have failed to see how dreadful a culture this was, but she was at home. Everyone here was intimate with horror and expected the worst. It is to Sheldon’s credit that she did not fall prey to the right-wing delusions of Patricia Cornwell, another self-hating lesbian romanced by the CIA and obsessed with violence, death, and guns. In her letters as in her fictional extrapolations, she was eloquent on the Dr. Strangelove psychology of the place. Were Sheldon to have written publicly about these things as a woman, let alone a feminist, she would not only have been trivialized but found guilty of serious disloyalty by Ting’s associates. Tiptree, however, could write from the perspective Sheldon shared with Ting, with some of Ting’s skill at negotiating life, and with Sheldon’s nominally left-wing, feminist politics.

Now, “he” was being called on matters even closer to home and threatened with charges of sexism. To respond to these pressures and write explicitly feminist stories, Sheldon created a third personality, thinly veiled as “Raccoona Sheldon,” whom Tiptree “introduced” to editors as a beginning author under his wing. Thus “he” could be assured of doing justice to feminist women. But while Raccoona Sheldon was much closer to Alice externally (she was supposed to be a middle-aged housewife with a family, a talent for drawing, and incurable horror vitae), she bore little resemblance to the fragile but lusty woman behind the Tiptree stories. Nor were most of her stories as good. They were written self-consciously in a different voice from Tiptree’s and betrayed their origins in Sheldon’s attempt to imagine what a “good” woman’s voice might be: pained and politically correct. Much of Tiptree’s subversion was gone, including his tough absurdist humor. Raccoona, in short, was much more of a fictional character than Tiptree had been and could not help but fall short in her task of expounding for once and for all where Sheldon stood as a feminist. The assumption that Sheldon slipped into permanent depression when she could no longer play Tiptree turns out to be only half the truth. Another big chunk of it is that she had tried, and failed (as she saw it), to be Raccoona.

For most writers, the disappointment would have represented a failed experiment, but for Sheldon it was a disaster. Raccoona bore a certain resemblance to Mary Bradley. As such, she was a construct but also a reminder of things Alice Sheldon would have preferred not to face in herself. Many of Alice Sheldon’s worst characteristics appear to have been inherited or imitated from Mary Bradley: the vanity, the inconsideration of others, the sorrow when it got self-indulgent. Long before Joanna Russ was administering Tiptree some friendly twitting over his relentless gloom, Mary Bradley was sounding very much like a bad Tiptree story: “Alli told a cute story about a newborn rabbit. Mary replied’”and Alli knew her response by heart, saw it coming on like a speeding car’”’˜You know, when they are shot they cry like babies.'” It may have been no accident that Raccoona Sheldon surfaced just around the time that Mary Bradley became terminally ill. Unconsciously, Sheldon may even have made the connection between her mother’s inevitable death and her own likely unmasking, and devised a persona to absorb both disasters when they struck. If the ruse failed, it may have been because Sheldon was very far from being able to own all that would go into Raccoona. Raccoona spoke with her mother’s despair and ambivalence about women, transferred now to the things which had promised salvation-science fiction and feminism. (In a final insult, Raccoona also tended to go on and on: most of her stories are longer than any by Tiptree.) It speaks for Sheldon’s great courage as well as her professionalism that she persevered with the Raccoona voice as well as the Tiptree, and produced two of her best stories: “The Screwfly Solution” and “With Delicate Mad Hands.” The latter came as close as Sheldon ever would to accepting her sexuality, with a protagonist who resembles her (the “red-hair-green-eyes-and-freckles kind” of girl) but has been disfigured by an operation (strongly reminiscent of Sheldon’s sterilization) and finds love with a piglike alien of uncertain gender. The former story is now one of Sheldon’s most famous, taking radical feminist observations about the aggression inherent in the male sexual response to their logical extreme. Aliens colonize the Earth by dosing the male population with a chemical that exaggerates this response, causing men to kill off all women and leaving the planet sterile.

It’s typical of Sheldon that this Dworkin-like parable reveals a streak of misogyny. In addition to the hostility to her mother, the anger at the feminists who would neither totally accept her nor leave her alone and the frustration of her lesbian celibacy all come together to create a nightmare with as much in it of wish-fulfillment as warning. It was her last act of rebellion. After “The Screwfly Solution” Sheldon would be crippled by the requirements of femaleness as she understood them, reduced increasingly to the “duty to mourn”‘”empathy, the defining feature of her female identity, as an obligation to perpetual pain: “In my head, the ‘˜bill of complaints’ against life is all interconnected; when I weep for Mary [Bradley], I’m weeping for Carthage and the baby shoes at Belsen. Thus trying to desensitize any particular instance ends by having to desensitize all… and any attempt to reduce [her pain] flies in the face of reality.” The obsession resembles those of the Nobel-winning Holocaust poet Nelly Sachs, but Sheldon’s work had other roots and became more and more a parody of itself. At the same time, Sheldon was trying hard to get better in her last years. She experimented with an array of psychopharmaceuticals, not always wisely. She also persevered with her writing, producing several novels and story collections before her death and two posthumously published volumes. Most of this late writing is likable and some of it is extraordinary, but Sheldon’s confidence was gone. It’s not clear whether she ever understood that she was of more interest as a female writer than a male, or had once been.

Another obvious feminist question is whether Sheldon’s loss of Tiptree and the nightmare of Raccoona reflected a parallel decline in her marriage, now that she had faced up to being a woman in such a male culture as CIA McLean, full of burnt-out killers. The answer appears to be no. The one thing that held Sheldon together in the last difficult years of her life was her marriage, which became closer and more loving as her mood darkened. Some have been tempted by the eventual manner of her death and Ting’s to conclude that Sheldon went from being a man to being a man-killer. The truth is more complicated. Though Sheldon wrote a great deal about male violence and from experience, she did not write against men in the manner of most radical feminists: she never seriously entertained the possibility that men could choose to be different than they were. Her concern with male violence drove her to misanthropy rather than female identification. Perhaps one of Tiptree’s functions had always been to defend her choice of a conservative man, who had seen as much evil as she and had more of a talent for happiness. As a woman, Sheldon was forced to recognize that she had also chosen a world in which she was superfluous, but after the first years of her marriage she was not inclined to leave it. The manner of her suicide indicates rather that the reverse was true. Though she was determined to commit suicide after Ting’s death, she was also sufficiently committed to life for most of the 1980s to plan to wait that long.

Phillips’ skills rise to their greatest test at the end, when she must contend with Sheldon’s mercy killing of her husband. The science fiction community and that of McLean both absorbed the tragedy as a double suicide. Phillips admits that by 1987 Ting was not competent to make that decision, though she does not go further in accusing Sheldon of murder. She had tried to get Ting to join her in suicide as early as 1979. Her self-centeredness in insisting on the suicide pact is somewhat vitiated by an unexpected twist: at the time of Sheldon’s greatest depression she apparently got Ting through another suicide in the family, that of Ting’s own daughter. Audrey Sheldon’s death may have made Alice unwilling to repeat his trauma by killing herself alone. What is clear is that with whatever amount of manipulation, Sheldon had got Ting’s agreement as of 1979 to a deferred suicide pact, to be acted on when they were no longer able to live without assistance. There is little doubt that this point had been reached in 1987, when Ting’s care exceeded Sheldon’s abilities and she was too emotionally fragile to live alone. It was known then that she died holding his hand; Phillips also tells us that she wrapped a towel around her own head, thinking of those who would have to clean up. The tenderness of these details must be balanced against her call to Peter Sheldon, telling him she had just killed his father, before she did away with herself. The reader is baffled in any attempt to place this call on a map of inner motivation: beyond Alice Sheldon’s compulsive organization of her life, was it remorse, or aggression, or a final seizing of center stage?

We don’t know, and Phillips never speculates about anything, sticking to what can be verified. (A few other messy details of Sheldon’s life, including the likelihood that she was a battered wife with Bill Davey, are left largely for us to guess at.) There is much that we can interpret about Sheldon with the information Phillips has pieced together, but more importantly, there is much for us to admire in the life of this tortured soul, whose legacy may now get the attention it deserves in a new century of violence. This book should raise anew the question that haunted Sheldon: what our ongoing age of atrocity means to women. For that alone, Julie Phillips deserves all our gratitude.