Dreamchild: A Film Essay by Elwin Cotman

“What was that name that Lewis Carroll used to call you?”

“What was that name that Lewis Carroll used to call you?”

“That’s right. Dreamchild.”

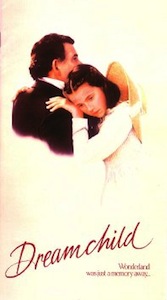

That is a beautiful movie poster. Made doubly so by the fact that, in the movie, the moment it illustrates most likely didn’t happen. Dreamchild, the first film made by the Jim Henson Creature Shop without the auteur’s input, is a film about memory. What happened, what we wish had happened, what we wish we could take back. It is also, like the poster, beautiful.

In college I worked at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Library. I was in the stacks department. We put books back where they belonged. I believe the department was famous for having Pitt’s longest-serving employee, a cantankerous old man who headed stacks for 30 or 40 years and always talked about his trips to the “picture show.” It was a job anybody could do and, accordingly, we were paid nothing. But it was comfortable, so comfortable it never occurred to me to secure an internship or some kind of real job at any point during my three years of undergrad. For two years I pushed around carts and tried not to fall asleep while shelf reading.

A great part of shelving books was the opportunity to lollygag and dillydally. I got plenty of reading done when I was hidden among those metal shelves. A particular favorite place to waste time was the magazine section, an impressive collection of hardbound magazines. I would dive into the old issues of Cinefantastique, the greatest ever journal devoted to speculative film. It was like having a time machine. I wiled away the hours reading articles about classic movies from before they came out. On-the-set reports from Temple of Doom and Conan the Barbarian. Reviews of Dragonslayer and Krull. Interviews with Joe Dante and Tobe Hooper during the height of Spielberg’s media ascendance.

One issue previewed a small English movie with an intriguing title: Dreamchild (1985). An intriguing title with an intriguing premise, based on true events: the 80-year-old Alice Hargreaves (née Liddell), the inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice, journeys to America to receive an honorary degree from Columbia University, in honor of the author’s centennial. In Depression-era New York City, she has several fantasy sequences involving characters from the novel, designed by the Jim Henson Creature Shop.

Let me repeat that.

Jim Henson.

Doing Alice in Wonderland.

In the eighties.

For a nerd, I am relatively modest in my fandoms. That said, I have watched Labyrinth from beginning to end at least one hundred times. Like many in my generation, I was raised on Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal, that classic duology of dry humor, genuine scares, big haired eighties pop, Froud faerie designs and breathtaking puppetry. They have achieved iconic status and deservedly so. The Henson fantasy oeuvre is all the more special for how little of it there is. You have the two features, Fraggle Rock, and The Storyteller TV series. It seems absurd that anything would pass under the radar, yet you will find many a Henson fan unaware of Dreamchild.

After learning of Dreamchild, it shot high on my list of films to see, and stayed there until–thank the gods for Youtube–I finally saw it this year. It’s easy to see why Gavin Millar’s film hasn’t achieved the cult status of the other two films, and not just because Henson didn’t direct it. Dreamchild is not a fun movie. The film is sad, elegiac, has a dark color palette and, for a movie full of animatronic puppets, startlingly understated. No goblin dance parties here. It’s not even a fantasy, per se; all of its speculative scenes are firmly rooted in dream sequences. The film takes place in the real world, the protagonist is elderly, and it deals with end-of-life issues in a frank manner. Dreamchild is a deeply thoughtful picture with a lot to say.

Before I go on, I must admit I know little about Lewis Carroll, real name Charles Dodgson, one of the most fascinating figures in English literature. I love Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, of course, and it’s way past time I gave them a reread. His complicated relationship with the Liddell family has been subject to much investigation, and centuries later there are still no concrete answers. Was Reverend Dodgson a harmless pedophile obsessed with Alice Pleasance Liddell? A mentor caught up in the Victorian cult of the child? Whatever the truth was, the movie falls firmly on the side that he loved Alice. The character of Dodgson is absolutely smitten with his prepubescent muse, and she has a certain affection for him, as well.

Dreamchild was made by the Jim Henson Creature Shop, not Henson, and it would be illogical to think he had any more to do with it than with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movies. Yet somehow it fits with the two Henson-directed films, to the point that I would call it a trilogy closer. I’m sure some will claim The Witches has that title, but hear me out.

The Dark Crystal is a full-blown fantasy world, every single detail down to the smallest flower a work of imagination. The story is pure monomyth, a child’s heroic fantasies (and nightmares) brought to life. In Labyrinth, the fantasy world is conquered by humanity in the form of David Bowie’s Jareth. Conquered and ultimately rejected by Jennifer Connelly’s Sarah, though she retains that fraction of whimsy that will help get her through her adult life. The climax of Labyrinth makes it explicit that the fantasy world is the world of childhood.

The first movie is a child’s dreams, the second movie about reconciling childhood concerns with those of maturation. Now we are at Dreamchild, which is firmly about the regrets of old age: the inability to change the past, the loneliness, the approach of mortality and the uncertainty for those you leave behind. The fantasy world that was so vivid in Dark Crystal is now dark and claustrophobic, the realm of fragmented adult memory. It is interesting to me that Labyrinth is also about a romantic relationship between a young girl and a much older suitor; in that way Dreamchild works as a spiritual sequel, the girl coming to terms with the relationship, now that she has nothing left to do but reflect on the past.

That the world of imagination/childhood is rendered so terrifying makes Dreamchild doubly effective. The Henson duology, particularly Dark Crystal, are often scary, just as childhood can be scary. The adult mind forgets the fear it felt the first time the Skeksis shambled onscreen in their hulking Baroque costumes, just like it tries to forget (yet subconsciously remembers) childhood trauma. Alice’s trauma stems from her girlhood. She begins the film by lying to herself, saying she was merely the template for Dodgson to create his stories. As things progress, her repeated question “What does it all mean?” goes deeper than simply wondering why so many people love a children’s book.

The Story

Dreamchild opens like a horror film: ominous cello music, camera panning over water that does not look entirely natural, to a beach tossed with debris. The Mock Turtle is crying; his fur is patchy, his oblong face is bewhiskered and a dark green color. The Gryphon looks somewhat like a Skeksi, unfolding wings so tall they stab at the top of the screen. They do the classic dialogue with the elderly Alice (Coral Browne), insulting and threatening the scared woman. She turns into the child Alice, who is not so frightened. “Where are you?” the woman thinks as the camera fades. “Where have you gone?”

New York City. The 1930s. We are introduced to the upper crust Alice Hargreaves and her timid assistant Lucy (an early turn by English TV actress Nicola Cowper). Alice is not particularly likeable. She is judgmental, self-possessed, obsessed with being proper, henpecks her assistant, and spends her time ruminating on curious American customs, such as this gummy paste they chew all the time. She’s the type of woman who insists on being called Misses Hargreaves. Needless to say, Alice is flabbergasted when they are met at the harbor by a horde of journalists who chase her down, thrust stuffed rabbits in her face, call her by her first name, and generally behave like nuisances. Alice claims to have no idea what the fuss is about, which begs the question: why is she there?

As if to prove this movie was made in the eighties, Peter Gallagher is in it. He plays Jack Dolan, an unemployed wheeler-dealer reporter who sets his sights on Alice as his meal ticket. To get to her he seduces Lucy, then decides to break the young woman out of her shell. It is up to Jack to explain the situation to the audience: America is in the middle of the Depression and everybody is looking for a little wonder in their hard lives. As such, New York City is gaga for the arrival of the “real Alice.” Alice in Wonderland is a story embedded in the human DNA: everyone knows the inquisitive little girl’s adventures down the rabbit hole even if they never opened the book or know the slightest thing about its author. The reporters who hound Alice certainly don’t know their facts, asking her who this “Dodgson guy” is. The idea of art taking on a life of its own is an important theme of Dreamchild.

The film flashes back to Alice’s relationship with Dodgson. These scenes are the linchpins of the movie and they play like scenes from a Victorian novel, patiently told. Beneath every scene is the intense longing Dodgson (Ian Holm) has for his muse. Amelia Shankley, a charming child actress who did some period pieces in the 1980s and early ‘˜90s before, unfortunately, disappearing off the face of the planet, portrays Young Alice. It is easy to see how the nervous, stuttering photographer becomes so infatuated with her. She is not the Alice of the books, but she is bold, smart, and mischievous. She is also knowing, and interested in Dodgson, if only because he is her first experience of a man feeling this way toward her.

In her very first scene, young Alice is already his confidante. She relates to her mother and sisters a story about Dodgson photographing Lord Tennyson. When her mother wonders with concern why Dodgson tells her so much, her response is, “Because he loves me.” She knows the emotion, if not the extent of the writer’s feelings. There is a preternatural sexuality to the way she interacts with this hapless man, showing her interest in the only ways she knows how: flinging water at him during a boat ride, offering to dry him off with her own handkerchief, knowing that she makes him nervous. The movie makes a bold move in having his affections returned. Her feelings for him aren’t sexual, and, if Dodgson feels sexual desire, he hides it. They exist in a strange place, child and man-child, with the child often having the upper hand. Taunting him, complimenting him, knowing when to give and hold back her favors. These scenes are filled with tension, and provide a dark undercurrent to the older Alice’s regrets.

Nostalgia

Dreamchild is not really a film about children’s literature, but our relationship to this literature. In exploring this, and the way it blurs the lines between fantasy and reality, it joins a unique sub-genre of fantasy film that deals with this topic. Finding Neverland and The Neverending Story are also in this category. The media is wild about Alice because she provides a nostalgic feeling in the midst of the Depression. Despite the economy, Columbia University is willing to throw large amounts of money toward this nostalgia trip.

Never mind that the book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is in no way comfortable children’s lit in the way that, say, Winnie-the-Pooh is. The book is oftentimes frightening and undoubtedly surreal. It is also, arguably, not really for children; stuffed to the brim with philosophy, satire of Victorian figures, and references to contemporary people, places, and events. In the 1930s, as now, many people’s fond memories of it had more to do with how old they were when they read it, and less to do with its bizarre cavalcade of disembodied heads, abused lizards, and pepper-flinging cooks. Lewis Carroll’s weird combination of a child’s rambling logic and adult cynicism has become a fairy tale: a story template endlessly retold through the ages. One need only look at Tim Burton’s recent adaptation, in which he bends the novel backwards, inside-out, then sets it on fire to turn it into a Lord of the Rings-style war epic, to see how far perceptions of the story have strayed from the context. Dreamchild, being a narrative of the conflicts between childhood and adulthood, is one of the more faithful Wonderland pastiches.

As Jack explains to Alice after barging into her hotel room, a world in economic disaster is very open to distraction. For her part, Alice is trying to work out her transition from muse to relic of the idyllic past. The idea of the nostalgic permeates every frame of the movie, with a running theme of how media is used to create fabricated visions of history. Much is made in the flashback scenes of Dodgson’s career as a photographer, such as his heroic portrait of Lord Tennyson. The advent of photography (and its subsequent influence on the novel) changed the Western world and Victorian England, specifically; what was lauded as a means of capturing reality was just as often used to fabricate romantic images, such as the angelic representations of childhood in Dodgson’s portraits of the Liddell sisters.

The movie positions Dodgson as a man-child trying to connect with his own youth through indulging his sense of whimsy. Fast-forward seventy years. A generation raised on his novels now gets their nostalgia through radio, as shown in a scene where Alice visits a recording studio. She witnesses the recording of a melodrama about a singing cowboy, the kind of popular Depression-era entertainment that had little to do with the real Old West. There is also mention of the 1933 Paramount Pictures Wonderland adaptation. It is also important that Jack is a reporter; the first scene in the newspaper office shows the editor-in-chief sending his minions after the “real Alice,” desperate to report something “fun.” Dreamchild illustrates a pivotal point in journalism, in which entertainment and celebrity are starting to be equal with, if not taking precedence over, world events. This is par for the course in the modern era, but Jack and his comrades are at the start of this shift.

Dreamchild positions these new and old medias against each other, an ever-evolving search for simplicity for an increasingly jaded public. This makes Alice Hargreaves truly unique: she is not a photograph, or a book, or a radio serial. She is a living totem of childhood nostalgia. “Better than Peter Pan, Huck Finn, and Santa Claus all rolled into one,” according to Jack. The 10-year-old Alice had no choice in becoming the subject of Dodgson’s art. The 80-year-old Alice willingly exploits herself on the radio for money, clumsily reading a monologue somebody else wrote, where she represents herself as the character from the book.

And all the while, Alice continues to protest that she does not understand what the fuss is about. Everything stems from her relationship with Dodgson, a burden that she alone is left to shoulder. Meanwhile, the world around her is trying to make something simple from the difficult life of a woman whose difficult relationship with a difficult literary figure spawned a difficult text, a private elder who has endured her share of personal tragedy. If Alice is the messy truth behind the art, then Jack Dolan represents the commoditization of said art. When Jack, armed with his charm and bare minimum of knowledge about Lewis Carroll, tries to woo the old woman by evoking her relationship with the author, it seems that, manipulative as he is, he “gets it” better than she does.

“Misses Hargreaves…We just want you to be the Alice we all remember.”

Her response: “It would be difficult enough at my age to be what I once was, but utterly impossible to be what I never was.”

There is bitterness in that line, as if Dodgson hurt her somehow by turning her into a beloved literary character. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter to the book’s admirers if she is the “real Alice.” A huge part of Alice’s dilemma is dealing with the fact that something so personal to her has taken on a life of its own, and making sense of her role in this. That dilemma is what she’s willing to acknowledge to others, but Dreamchild goes even deeper.

The Inner Mind

This is as good a time as any to talk about the puppet work. There are six puppets in the movie: the Caterpillar, the Mock Turtle, the Gryphon, the Mad Hatter, the March Hare, and the Dormouse. The Wonderland characters have aged with Alice; decrepit, sickly versions of Tenniel’s illustrations, they are brusque and insulting to the old woman in her fantasy sequences. They also stand up there with the best of the Henson Shop’s work. Just look at the disgust in the Caterpillar’s eyes when he asks Alice: “So you think you’ve changed, have you?” It’s amazing.

As stated, the young Alice in the fantasy sequences is perfectly capable of keeping up with the Wonderland characters. It is when she switches to her current form that their well-known dialogues confuse her. Her inability to deal with her past has only been exacerbated by age. The puppetry sequences in Dreamchild serve to delve into the complexities of the human heart. Herein lies the power of this movie: in a medium known for being explicit, it allows the characters to say one thing and think another.

For instance: in a particular scene halfway through the movie, Alice is getting ready for bed. She has a lovely conversation with Lucy about how she has become used to the fact of her death. She believes death will come as a friend, that God is a gentleman, and she looks forward to seeing her husband and sons in Heaven. While the old woman sleeps, Lucy goes dancing with Jack. Alice is awoken by a ringing telephone; addled and helpless without her assistant, she walks into another room to find Dodgson sitting on the edge of the bed, staring condemningly from the afterworld.

At this point, the movie delves into serious psychological horror territory. Alice is about to answer the phone when she looks into another room and sees the Mad Tea Party. The March Hare is ugly and insolent, with crooked incisors and a wildly twitching nose. You can smell his bad breath through the TV screen. The Mad Hatter is even uglier, and appears to have partaken of the wine that the March Hare offers. Once Alice sits down, they go about the famous dialogue word for word, but their delivery is sinister. The Hatter is violent, knocking hot tea everywhere, pouring it on the Dormouse’s nose. The March Hare keeps sticking his ugly snout in Alice’s face. The question of “How is a raven like a writing desk?” is thrown at her like an accusation, her inability to answer the answerless riddle only more proof of her helplessness. “Wrong, wrong, wrong!” says the Hatter, scattering dishes. When Alice accuses them of wasting time, she is really talking about herself.

“You half-wit,” the Hatter calls her. “Ugly old hag. You should be dead, dead, dead.”

Past and present merge. The scene is juxtaposed with a flashback of an enthusiastic Dodgson telling the story of the Tea Party to the sisters during their famous rowing trip. Young Alice muses on how she wishes the characters were real, while at the same time the characters scare the elderly Alice. The scene ends with the old woman trying to make sense of the solicitors on the other end of the phone. She is completely at her wit’s end, unable to reconcile with her past and her shortening future. As beautiful as her conversation with Lucy is, the film makes the point that no amount of age can prepare someone for mortality. Furthermore, the Christian afterlife might be just as full of people you have wronged as those you wish to see. The puppetry sequence is employed to truly get inside Alice’s head, weaving the past, present, and fantasy worlds seamlessly. This is masterful filmmaking.

Gallagher and Cowper are fine as the young lovers, but this is Coral Browne’s movie. It was the final feature for the legendary Australian actress, and it is impressive to think how the proper character she portrays is so opposite to the famously ribald thespian. Her performance is understated and completely natural. Browne is a beautiful woman with an evocative face, and she does a lot with the character of Alice Hargreaves: at turns self-absorbed, frightened, confused, reflective, blunt, greedy, a liar, vain, and full of humor. One has to think that the thoughts on Alice’s mind were most likely on Browne’s, as well. The actress would pass away six years later.

The puppet scenes are used to get to the meat of Alice’s trepidations. “Repeat after me,” the Caterpillar says. “You are old, Misses Hargreaves.” For the life of her, Alice cannot remember why her mother burned Dodgson’s letters to her, or why he was forbidden from coming around her and her sisters. It is unclear whether she has forgotten due to age or because she made herself forget. Among these things she has forgotten, she gradually comes to acknowledge the truth of her feelings.

“I used him,” she says of her first suitor.

Love

At its heart, Dreamchild is a love story. Not love with a capital L, but the down and dirty love that leaves people sick and opens the door for catastrophe. All of the events in the movie stem from the sad, doomed, and unhealthy love between Dodgson and Alice.

Towards the end of the film, there is a painful flashback in which Alice, alone with Dodgson in his dark room, expresses her excitement over having tea with a group of boys, including a certain young sportsman named Reggie Hargreaves. The pain is clear on Dodgson’s face, and he comes this close to telling her his feelings. The words of love are right on his lips. Instead, he stammers some advice about not falling for the first lad to sweep her off her feet. Naturally, she doesn’t get it. It kills him inside when he hands her a copy of his book, this testament to his affection, and all she sees is a story. Then the kicker: Alice races off to join her sisters, blithely tearing back the window curtain, exposing his pictures to light. Dodgson is left alone, spurned, and all he can do is laugh at the absurdity of it all.

It is not Alice’s fault that she did not love a much older man, but the trip to America dredges up all the scars. She feels terrible about the way her relationship with Dodgson went. She cannot remember whether it went to an inappropriate level, but the guilt she feels for his banishment from her life is like that of a woman who has rejected her lover. This is underscored by a flashback towards the end where Alice and her sisters, the dashing Hargreaves boys in two, ask Dodgson for a song. He stutters through the “Mock Turtle’s Song” and they laugh at this dweeb, already engaging in adolescent cruelty. Young Alice can’t help herself, but the woman she grows up to be feels guilty for the fact that she literally outgrew her first love. “I used him.” In her mind, she entertained herself with his affection and cast him away, and there is no chance now to make it up to him.

Cinefantastique described the plot as the elderly Alice helping to bring together two young lovers. Thankfully, the movie is not nearly so trite. It is about love in all its hardships. The romantic B-plot is itself complicated and, in a realistic turn of events, largely unresolved at the end. Lucy is unsure of whether Jack wants her or if this is all a ploy for money. It all comes back to children’s literature. Alice is the complicated truth behind the beloved art. Jack is its commoditization. Lucy is the innocent in the scenario, with this sojourn to America her own coming-of-age story, her introduction to the world’s complexities.

That the love story does not quite work is to the movie’s favor. It is possible that Jack is charmed by this beautiful and nervous young Englishwoman; equally possible that his feelings are paternal and condescending. It is possible that Lucy sees the vulnerability under his snake oil routine; equally possible that she is latching onto the first man who will have her, transitioning from an ailing mother figure to a lover she can depend on. That Alice is so impressed by their “love” speaks more about her than them. When we last see them at the celebration at Columbia, Jack is sitting next to Lucy, having successfully insinuated himself into both women’s lives. Whatever love they have is the kind that will not solidify in three days, and the movie does well to leave it open-ended. This is no twee romance between Lucy and Jack. The possibility is there for a relationship just as traumatic as Alice and Dodgson’s.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was Dodgson’s love letter to Alice. It is in realizing how far this story has gone beyond their personal relationship that Alice finds her peace at last.

Real People

The ultimate strength of Dreamchild is that it allows its characters to be complicated. This is a film about real people. Real people agreeing, disagreeing, loving, and clashing. It follows the interrelated relationships of four nuanced characters: Alice, Lucy, Jack and Dodgson. Does Alice love Lucy as a daughter or see her as a servant? Does Lucy depend on Alice because she needs a job, or because the way the old woman speaks makes Lucy, according to her, “see through her eyes.” Does she fear Alice’s death for Alice’s sake or hers? Does Jack want Lucy or is his quarry the old woman? Is he in it for the money? Is he a sympathetic con artist or a crass con artist taking twenty percent of Alice’s earnings? When Alice decides to do the radio show, is she doing it to work out her feelings or because she wants lots of money? Does young Alice love Dodgson or is she playing games with him? Does Dodgson appreciate her family at all, or is his whole mentor routine just to get close to his beloved?

The answer is, wonderfully, all of the above. These characters are written in shades of gray, and the fact that they constantly use each other still allows for genuine feeling. They’re human and are allowed to be as complicated as human beings are. The same goes for their relationships. For all the abusive undertones in their interactions, Lucy seems to be the only person who truly understands Alice. Mrs. Hargreaves expresses her affection the only way she knows how, and it is possible her relationships with Reggie and her sons were just as stilted. In navigating her first experience with a male suitor, Lucy grows disillusioned with both Jack and Alice. She lashes out at them, but she still loves them.

It is in seeing how art moves beyond the personal that Alice finds her solace. At the ceremony, she flashes back to that painful rendition of “The Mock Turtle’s Song.” As a men’s choir performs the song, Alice uses her imagination to rewrite history. Instead of laughing at Dodgson, she hugs him, an embrace that hits the man so hard he can’t even return it, but lets his arms drop to his sides. He is so lovestruck that he can only receive. Seventy years later, Alice is now the artist recreating the world as she wants it. It is telling that Alice, prior to this a scared victim of her memories, takes control of the world of childhood/fantasy by embodying her former self. This makes sense, as the child-self is the version of her most comfortable in that world. Listening to the choir, she appreciates everything Dodgson accomplished in a way that her girlhood self never could. This is a revelation that could only come with age. Whatever occurred between her and the reverend, the product of their relationship has flourished beyond them as individuals. It is now a part of the world, and this fact helps her go to her rest in peace. At least, that’s what I got out of it. This being Dreamchild, the final image on the Mock Turtle’s beach is both creepy and heartwarming.

Dreamchild is that rare movie, fantasy or otherwise: a film made for adults. You have trauma on the inside, the Depression on the outside, and there are no easy answers. You are required to think. Was the historical Dodgson romantically interested in the young Alice? It doesn’t matter. This movie is not a biography of Dodgson or Liddell: it is a treatise on how art takes on a life of its own. It examines how art stems from individuals, and how it affects individuals. With this in mind, the movie works better because they’re not striving to tell the 100% truth of anything.

The movie is also a swan song. Both Browne and Henson died shortly after its release. Henson left us with a few more creations before his untimely death, projects that he was more personally invested in. However, his genius is all over the puppetry in this movie. As such, Dreamchild is an opportunity to see two master artists at the top of their form, before they became a part of history.

For a movie with so much to say, Dreamchild is both short and inconclusive. I feel myself drawn nowadays to storytelling that does not tie everything up. As the character of Dodgson shows, even death is not the end. The story will go on, and as long as there are human beings, we will retell it in our own ways.

Elwin Cotman was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1984. In 2005, he graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a degree in English Writing. In his time, Elwin has been a Wal-Mart employee, bookseller, middle school teacher, youth counselor and ESL instructor, and has finally found a job that pays less than any of those: fantasy writer. He currently resides in Oakland, California. Follow his blog at http://www.lookmanoagent.blogspot.com.